Uma Kurt’s The Tie:

Smaller Is Better When Little Theatre Is a Powerhouse

By Diane Sippl

You Should Have Been There

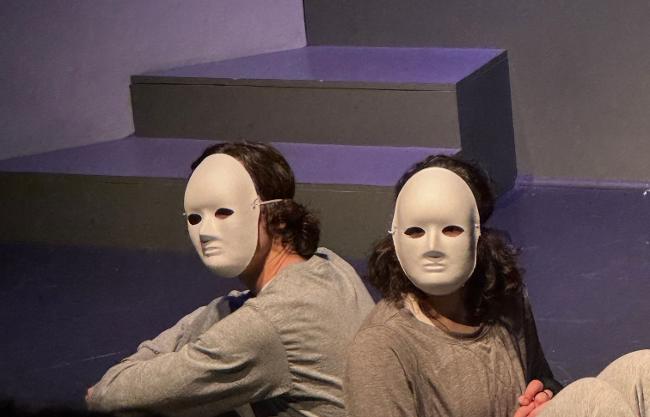

Kneeling behind her, the male actor places a white mask on the female actor, who’s sitting on the floor, downstage center, and then he places another mask on himself. They turn and sit back-to-back like two bookends encircled by one rope, both faceless even if for opposite reasons.

Female (to the audience): “It never should have ended like this…”

Male (to the audience): “It never should have started like this.”

(Lights fade to red, then black.)

An end that circles back. It would be the end of the play, except that by now we know it’s on us—the experience of the theatre has spilled into our lives, become part of us, spurring us to act.

Yet the masks, the rope, The Tie—what do they imply?

Let’s back up to a year ago. A petite high school student, age 16, exceedingly talented, responds to a scolding from her teacher by pulling herself together and scripting a drama. Not the usual kind—she bases it on questionnaires distributed to classmates and friends too self-conscious or afraid to participate in up-front interviews but compelled to cooperate on anonymous written forms. Their school is in Sarajevo, a place many of us still see as either a once-upon-a-time Olympic winter wonderland lost in the Alps or a war-torn locus of destruction under all the world’s gaze. Yet Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is the seat of a thriving tradition of experimental theatre, the breeding ground of a teenager’s vital harnessing of emotions and expression. It’s also a place like all of our towns, schools, and homes, where every day, what shouldn’t happen, happens, where what we shouldn’t do to each other and to ourselves, we do.

The Light's Inside

“Ladies and Gentlemen, good evening and welcome. Take a picture and remember this image: every theater in L.A. should look like this every night, and that goes for every year!” says Nenad Pervan (better known as “Neno”) as he introduces himself—Il Dolce Theatre Company's founder and director and the executive producer, director, and acting mentor of The Tie.

With the 54 seats on the main floor sold out, the balconies that line this little theater are brimming with “standing room only” enthusiasts there to champion the cast of two, radiant student actors Uma Kurt (also the playwright and translator of The Tie) visiting from high school in Sarajevo and Andrew Solari from Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, performing his Senior Thesis for his B.A. degree under the supervision of his professor of acting, Neno Pervan. In this smaller hall, “The Other Space” of the Santa Monica Playhouse, under the aegis of its longtime theatre activists and co-artistic directors, Evelyn Rudie and Chris DeCarlo, for this 64-minute production with no intermission, these two young actors share the limelight.

But tonight, the light’s inside—a luminosity of language the artists share with us to demonstrate, conjure, question, ridicule, and condemn in their commentary on loss, needless loss that The Tie points out is produced by us. Yes, this theatre event implicates us, its actors speaking on occasion directly to the audience but also positioning themselves within it, a community of spectators, onlookers who themselves have neither the integrity nor the courage to speak up. YOU SHOULD HAVE BEEN THERE!

Programmed by what we stream on our screens, we tend to regard teenage issues through a pop-culture veneer that flattens and brands them: “boy trouble” and “girl trouble” in whatever way they fit or don’t fit; social media addiction; peer pressure to conform; rebellion against parental control; drugs and alcohol. Yet what lies beneath and behind the labels, and how do we unearth it? In a sense, The Tie twists everyday introspection inside-out. We get to see ourselves as both victims and accomplices. “Up-close and personal” becomes a universal byword: who we are is determined not by where we live but by where we stand.

Peel it away: Suicide—rape—social and emotional abuse—denial and indifference on the part of bystanders—phobias that lay the foundation of what “must be” whispered about, gossiped about, shunned, politely ignored. And the antidotes: Dreams, humor, dance, therapy, empathy. These matters are what The Tie dredges up, from the soil beneath our feet everywhere, every day, enacting them in plain sight. It’s a tall order for little theatre, but the teenagers know their stuff. Take it from them, with a novelty of expression at every turn.

Unspeakable

“The tie.” Does it bind—or kill? Maybe both. The Tie opens by stretching out this question, physically in the first moments as two actors play tug-of-war with a rope and sometimes loosen it, as if facetiously but more likely, sardonically. It’s a motif in the hour-long performance in which “the tie” gets looped and noosed, lassoed and knotted metaphorically as well, to rope in peers, parents, teachers, counselors, and the community-at-large in a work that encompasses the willful ignorance and indifference—often devastating oppression—of fundamental social structures and systems. Foucault would have a field day here. Freud and Jung would be turning over in their graves. Instead it’s more like we’ve entered the playground of Ionesco.

The Tie gives us 11 piercing scenes, each with its own title. The first, Funeral, is both riveting and demanding: in a mere 15 minutes, it introduces a panoply of techniques the actors will use to engage the audience. On a relatively bare stage where specifically realistic sets and props have no place, even the “costumes”—gray sweats—do nothing to distinguish the actors who are not playing characters with names; so for discussion purposes, let’s refer to them simply as “He” and “She” as they enter the stage from the rear of the hall. Each body tied to its chair, with their backs to each other, She indicts Him of “ignorant bliss” when a girl they know was violated by boys they know. The girl begged Him for help. He watched but turned away. He claims He had no choice, that it wasn’t His fault. The argument ceases and we’re at the funeral. For a moment, She rocks in her chair, playing the girl’s mother. He narrates the tenor of the day directly to the audience:

They lied to her, and told her that her daughter was wonderful, and bubbly, and always had a smile on her face. Nobody had the courage to look her mother in the eyes and tell her that her daughter killed herself because of all of us who are sitting here today… Maybe she knew that her daughter was dead for a long time. Maybe she knew that we killed her. Maybe she killed her, too.

Then She becomes a funeral attendee. To the mother: “Take care, and stay strong, for her,” just as She expresses her hidden thought to us: “Oh My God, their daughter killed herself!” In another voice, She begins a poem, in English, then in Bosnian, and they continue:

He: Looking at the starry night. Your last breath echoes through my childhood. And in a single star, I see light, your warm, silver smile. And on a single autumn night, every leaf that lies to rest is one memory.

She: It tickles me, until the wind blows it away, into the empty. And in that empty, I wait for you, to fulfill our unfinished childhood.

Then She lets out a big sigh and stomps Her foot to change persona. “Say something, Jesus!” and He unties himself, stands up, and accuses Her of denying their role. “We pushed her,” He pleas guiltily, and She: “I didn’t push nobody off a building, and trust me—I wanted to many times.” Angry, He ties the rope around her, binding her to her chair, claiming they should have talked to someone. She laughs, “Ah, so you’re off in your head thinking you’re some kind of hero, or whatever bullshit. Sure. Ya, nobody liked her. Some hated her. And some were just frustrated pieces of shit. But that is not my problem.” She unties herself and He addresses us: “If only I could solve this fabulous enigma. When did we all become animals?”

In a brush with the absurd, on that cue, He and She morph into a dog and a frog, barking and croaking, leaping and charging across the stage. It brings boisterous laughter from the balconies, and we forget to take stock of the fact that the two actors have been transforming fluidly in ethical stance, personality, attitude, and even species through the whole scene in stream-of-consciousness transitions hardly noticeable. The mode of delivery has changed at least eight times. Are we playfully genre-hopping or sincerely shopping—for the most rhetorically successful way of approaching a topic often perceived as either untouchable or cliché?

Performance within Performance

In Scene 2, Food Chain, the animal motif continues but the mode shifts to something new again: linear storytelling. In a verbal contest of memory and speed within the fable genre, She packs a punch in both plot and metaphor: the human that “can kill whatever it wants for whatever reason” can itself get killed by a “tiny little bacterium” (think COVID-19). The clever recitations and fast pacing here add a note of irony to the dark context, which He caps off with a moment of absurd horror.

They are breaking the fourth wall (as in Epic Theatre code) in nearly every scene, such as in Adult World, speaking directly to the audience. After Her earnest four-minute monologue lamenting the increasingly frustrating chapters in life that lead to so-called maturity, He responds with his own snide two-minute diatribe on adulthood, including asides to the audience, playing it for slashing humor, especially when He leaps up from sweeping the floor and responds to his “wife’s” nervous fit over how to dry the laundry by breaking into a tabletop dance with the broom as a microphone and then as a guitar. In rock-style and mocking Her, He delivers the pop song, “I’m Still Standing.”

Let’s Go sets the stage in our imaginations as She fantasizes a lone cabin in the woods, a mountaintop escape from all judgements and directives on “how to live.” Trees, vegetable gardens, orchards, animals—freedom. But an inventive scene transition awaits us. Gazing up at the balcony, She asks, “Uh, what’s it say up there?” and He replies, “Selfish fools.” So much for dreams. The next scene opens with a volcano of venom— “Nerd! Asshole! Faggot! Bitch! Weirdo. Freak. Scumbag. Psycho. You’re worthless. You’re ugly. You’re fat. Kill yourself!” It escalates into a desperate “chair dance”—their rotating lines are recited in a rhythmic routine of stepping up and then down from two adjacent chairs, His and Hers, both facing the theater hall.

In No Solution, they spit out a five-minute litany of dates and deeds that may once have been poured into their diaries but are now decried by this two-person firing squad at the audience (or the jury, as they, on the witness stand, spew out testimony). Repetition of motion is paired with variation of injury. Each actor takes turns popping up like a jack-in-the-box slowly losing its vital spring (i.e.—its youthful energy and spirit) to denounce abuses at school. It’s a revolving choreography of accusations, a traumatic poetry of emotional isolation, that ricochets back like a battering ram of assaults, both physical and psychological, transported to the arena of spectators as if incriminating them as bystanders. They take to the aisles of the theater hall, and from the rear, they issue pseudo-pedantic tirades to the audience— “Report, or Run? Fight, or Flight?” Throwing their arms up in defeat, they disappear into the wings of the stage.

Sometimes the move to a new theme or angle is fluid, but other moves jump for shock effect or simply for a reprieve through a change of tone. A crowd-pleaser like Parents’ Meeting, which transpires on the imaginary school baseball bleachers, plays an overzealous father (He hoots for the team while His son, “Bob-bayyy!” is benched in the dug-out) against a detached, alcoholic mother who forces on Him a “healthy” swig from Her flask. Their initial banter offers a recurring opportunity in The Tie for intertextuality, in this case the man’s citing of the recent film, Eileen, (about a young woman’s radical comeuppance against an alcoholic and abusive father.) Never simply a catchy device in her work, such a reference by Ms. Kurt lends a timely voice to the play and allows her to make it her own, as when She wryly accepts His labeling of Her accent as “Bostonian” after She tells him She’s “Bosnian.” An in-joke and another signature line by the playwright (and actress), it steals a belly laugh from the audience amidst the play’s troubling subject matter. The mother proposes a play-date between the man’s son and her daughter, and then a date with Him just for Her—His hint to skedaddle!

Another Reality

A scene like To Love reminds us that in this play with plot lines that go nowhere, or at best in circles but with unresolved situations, and with no distinct or consistent personalities developed as characters, a theatre of the absurd is enveloping us. We find ourselves in a meaningless world in which the individual is isolated and communication appears futile—unless it is surreal. If in an earlier scene of domestic life, we saw the two actors engage in a hand-jive with the silverware at the dinner table, here He is amusingly adept at conveying the subconscious feelings of a lovelorn child. Seated, He is the manic manifestation of such trauma as His palms (faced up or down) and arms (stretched forward or crossing to his shoulders, head, or waist) do the talking far more effectively than words, at least as He narrates the conflict while physically presenting it. As if on cue, His hips take over for the parents’ neglected words, “I love you.” He stands for hula-hoop swivels that get squeals from the crowd, but in fact, as His emotions rise, He’s fit to be tied. His swivels repeat, at four more intervals, as He obsessively performs the sexual innuendo that hovered over the family when love was lost.

The scene is culminated in a full-fledged dance, a “rope dance” beginning with orange and green lighting for each of their respective zones. Then from these opposite sides of the stage, He “reels Her in” as she spins toward Him from Her violet to His magenta light. She uncoils, but fast and frantic. They repeat this, on a “shorter leash,” in red light, and on the taut rope. She tries to flee, in every direction, until She falls. It’s a marvelous transition to the next scene, figuratively linking a mother’s suicide from To Love with the rape of a teen in That Day. These two scenes mirror each other in His/Her episodes of lay psychodrama, both anchored in obsessive body movements but separate ones.

In That Day, compulsively repetitive verbal language ensues between She, boxing, and He, receiving the punches, as He urges Her to report what happened and She refuses. When She finally does narrate her rape, He washes his hands of it (as if guilty) and walks off while She lapses into a surreal self-dialogue as the past moment and present memory fuse. Her lines even include imperatives to the rapist to end the assault, whether they were ever voiced or not, either to herself or to the rapist. Throughout it all we hear His recurring lines of denial, as if He is the accused even when He, as the trainer/therapist, has been playing the role of the rapist’s friend.

The tragic event of That Day is the core of The Tie, and any iteration of it here can’t hope to do justice to its power in the live performance; but suffice it to say that if To Love commanded a theatrical vocabulary that joined His realistic verbal memory recall and His surrealistic body language, That Day flips the combination: Her real, physical punches coupled with Her stream-of-consciousness memory—and Her own surreal outer/inner dialogue in tandem/tension with His all-too-familiar, real monologue of innocence to the audience. In hindsight, the dance sequence in To Love now becomes a reminder that the rope is a weapon for control of a victim but could also be a way to “rope in” a perpetrator or collaborator, an accomplice in the crime of indifference, or to indict one for failing to be a whistle-blower.

The Thespian as an Artist

Fueled by commitment, wearing everyday sweats, the two actors present dire themes on a stripped-down stage using revolving theatrical languages, but this is no dismal production. Pulsing with dynamism and youthful energy, the play surges forward at 90 mph. In this inescapable whirlpool of contemporary life, no cell phones light up the hall for the usual texting, posting, and e-mail scrolls. No one moves. You sit with your fists clenched, hoping the world is not this way, or you belch a belly laugh because laughter releases fear and dread.

While in general, the underlying tenor of Uma Kurt’s voice is one of urgency, she modulates it from the accusative to the sarcastic, the earnest to the jocular. In Let’s Go, when she conjures a countryside idyll, a cottage in nature, she is downright dreamy, and some passages within other scenes are utterly lyrical, such as the recitation of a bi-lingual poem of loss in Funeral. There are lines that stick—She talks of that tender age when “no guy wants you but every man does,” and a bit later, He must answer Her cagey questions, “Any crushes? Love interests? Relationships? Situation-ships?” (Don’t we all have those?)

The mirthful cameo Parents is almost a scene stealer from the rest of the show. Andew Solari owns his performance like a true chameleon, forever changing color to fit the kaleidoscopic contexts of The Tie, wielding its rope to shift the turf or the tone. His moves are both rangy and agile (think Bill Nighy’s chair slamming in Skylight and guitar hamminess in Love Actually). Yet it’s Uma Kurt’s unrelenting stamina that prevails, whether in her accelerated daily workout for You Are What You Eat or in her punch-out venting of tragedy in That Day (both facilitated with diabolical finesse by her “coach,” Solari, who enforces the pace and the intensity like a human stopwatch).

It’s important to remember that the writing, staging, and performing of The Tie give us the sophisticated theatrical vocabulary of an old pro, yet the play has been conceived, created, and delivered by teenagers, namely the formidable playwright, actress, choreographer, and dancer, Uma Kurt, who even translated her sensitive and worldly-wise script from Bosnian to English. Throughout this elaborate process, the play sheds all sentiment and evokes the foreboding themes of Spring Awakening and Romeo and Juliet (producer and directing and acting mentor for The Tie, the astute and gifted Neno Pervan, has recently directed both these classics—Wedekind in Bonn, Germany, and Shakespeare in Santa Monica, California). An Expressionistic approach accounts for The Tie’s nameless characters who share their feelings by simplifying or distorting reality rather than using it on sets that are themselves symbolic, as is the stark lighting. Less is more; and smaller is better.

Still, and best of all, The Tie raises questions—not only about adolescence from A to Z, but also about the language of theatre. In an absurd world where both teens and adults once bowed to social media for communication, with all its verbally crippled and truncated texts and tropes, now they willingly submit to artificial intelligence, where the interpersonal realm includes robots. How does this stack up with the tenets of Theatre of the Absurd held by Grotowski and others: “actors must think with their bodies”?

The Ghost Is Real

In fact, is it a ghost—the anonymous deceased female alluded to in the play—who is the real “protagonist,” for want of a better word, in a staged performance that never follows an Aristotelian story arc but contextualizes and highlights the presiding off-stage action (“unspeakable” and therefore “unknowable” events)? In its series of vignettes—mimes, movements, choreographies, spoken reflections, inner dialogues, quarrels, dreams, fights—that beg our awareness of the invisible, The Tie can become a tool that moves from the stage to the world.

What is our role? Ultimately, we the spectators—more like participants, in this rapid-fire tour de force—are galvanized to answer for what happens, if that means opening our eyes, ears, and hearts to what is felt by our youth today, even when it is said in myriad ways beyond words. Yes, “our” youth, young voices, be they vented or shrouded or simulated or turned inward to silent introspection.

A white mask: does it imply death—that the female subject of The Tie is dead, a ghost? Or, speaking for her two mates, masked as bookends in the tragedy, that their hearts die with her, perhaps out of unrelenting empathy, even sharing her sense of utter defeat? Or that both masked actors are ghosts, anonymous, standing in for all of us who said or did nothing or not enough to prevent the loss? Uma Kurt’s unerring and utterly stimulating work of dedication lets us begin when the stage lights dim.

The Tie

Written and translated from Bosnian to English by Uma Kurt, based on the original play in Bosnian, Vez, written and directed by Uma Kurt; Produced by Il Dolce Theatre Company at Santa Monica Playhouse; Executive Producer, Directing and Acting Mentor: Neno Pervan; Stage Manager: Bonifacia-Erlinda Montano.

Performed by: Uma Kurt, actress; Andrew Solari, actor (as Senior Thesis – Acting, Loyola Marymount University, BA/College of Communications and Fine Arts/Theatre Arts).

Production of the English version of the play made possible by the joint effort of Il Dolce Theatre Company, Loyola Marymount University LA - College of Fine Arts and Communications, Theatre Arts Department, Center for Reconciliation and Justice, and Santa Monica Playhouse.

Performances: Santa Monica Playhouse (The Other Space)

1211 4th Street, Santa Monica, CA 90401

Saturday, January 27, 2024 at 5:00 pm and at 8:00 pm

Q&A Session with Marina Stanic, PhD, actors, and producer following the 5:00 pm production

Special Thanks are owed to Sr. Judith Royer C.S.J. and Sr. Maryanne Huepper C.S.J.

Supported by the 2024 Center for Reconciliation and Justice Annual Symposium