1-13-12

Sing Your Song: Belafonte Shows What It Means to Act

By Diane Sippl

At a Gathering for Justice, Harry Belafonte listens to youths express their dreams for social change in Sing Your Song.

My Song: A Memoir Harry Belafonte with Michael Schnayerson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

Sing Your Song Director: Susanne Rostock; Producers: Michael Cohl, Gina Belafonte, Jim Brown, William Eigen, Julius R. Nasso; Editors: Susanne Rostock, Jason L. Pollard; Music Composer: Hahn Rowe. Narrated by Harry Belafonte; 80 interviewees, subjects, and performers. 104 min., B/W and color, in English.

Sing Your Song: The Music Harry Belafonte, Sony Masterworks, 2011.

All photo credits: Sing Your Song, an S2BN Films release, 2012

All of us see the world as it exists; fewer envision what it might look like if made to change; and fewer still try to put together the people and ideas that make change happen. Paul Robeson was one; Martin Luther King, Jr. was one; Bobby Kennedy became one. And, of course, Nelson Mandela. I had just enough vision to see that they were visionaries, and to do what I could to help.

Harry Belafonte, My Song

Early on for Harry Belafonte, “acting” came to mean social and political “action,” and singing was a path to it, or let’s say, a vehicle.

If his enthralling and indispensable memoir, My Song, devoured in either sips or gulps, catapults us to other times and places with both urgency and verve, it also offers a deep reservoir of reflection into which the author has poured his faith and hope for nearly 85 years as he has ceaselessly asked the question, “What do you do now?”

Three Giants

What we learn on these pages is not only how Harry Belafonte has been “of his times” — an expression usually affirmative enough — but also how he has made his times, in good part personifying the struggle for civil rights in America beside his idol and mentor, Paul Robeson and his close friend and confidant, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In-between the towering scholar-athlete-actor-vocalist-activist Robeson and the younger, smaller, philosopher-orator-organizer-leader King, both with their booming voices and formidable devotion to purpose, marched the smiling, beguiling, tender yet relentlessly tenacious Belafonte, his own versatile voice commanding a charisma like no other, sometimes shrewdly behind the scenes and at other times bravely in the front line. His memoir accounts for precisely how he used the limelight to do this. Looking back over his life recently, he surmises: “I was good as a singer, but I wasn’t the best, and I’d known that from the start. I’d had to rely on my acting, and in the end I could make a case that I was the greatest actor in the world: I’d convinced everyone that I could sing.”

Just how much and how well Harry Belafonte parlayed his distinctive gifts as an actor and a singer into a lifetime of political activism — and why — is deftly elaborated in his book. One lasting impression in reading My Song is how astonishingly hand-in-glove this three-pronged plan was, and yes, it was a plan ever since his feisty childhood when his mother, angry herself, told him, “never ever go to bed at night knowing that there was something you could have done during the day to strike a blow against injustice and you didn’t do it.” He thought of this instruction as his Rosebud — “the moment that imprinted itself on me more lastingly, and meaningfully, than any other.” According to his mother, there was nothing in life to which he could not aspire, and nothing beyond his reach.

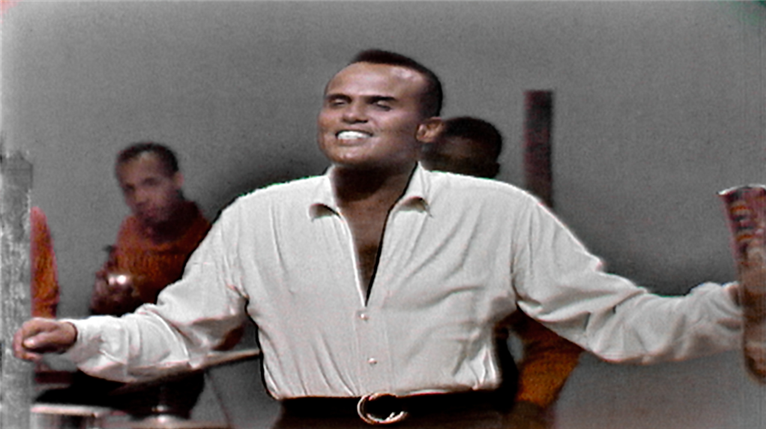

Harry Belafonte performing “Cocoanut Woman” on Bell Telephone Hour

My Song

This invaluable lesson frames the book, certainly the author’s heights but even his defeats, as the message resonates throughout his life to this day. Belafonte was born poor in Harlem in 1927 to mixed-race West Indian parents, a mother who moved from Jamaica to NYC and did domestic work, and a father who was a chef on the banana boats that ran between New York and the Caribbean. Often left to care for his little brother while his mother worked in his father’s absence, Harry was tough on the streets. He liked “playing for purees” with his pals, one basis on which he would later enjoy gambling with the “high rollers” in Las Vegas. His parents were both drinkers, and his father’s violence filled him with terror. When his mother took him away from such influences to live as a child with his white grandmother in Jamaica, Harry Belafonte first heard the everyday sounds and voices of peasants and workers that would become the music of his life.

Perhaps, in the end, where your anger comes from is less important than what you do with it.

Harry Belafonte, My Song

Growing up in Harlem was a difficult adjustment upon his return as a teenager, and rather than finish high school, he enlisted in the Navy. While he was a munitions loader for almost two years at the end of World War II, he read W.E.B. Dubois and learned about his work. This knowledge contributed to his awe of Erwin Piscator, the German who had founded a proletarian theatre in Berlin and now headed the Dramatic Workshop at the New School for Social Research in downtown New York. Belafonte would spend his allowance from the G.I. Bill to join Piscator’s collective there with students such as Marlon Brando, Walter Matthau, Rod Steiger, and Tony Curtis as they rose to become some of the finest actors of the day. But there was one crucial step that had to happen before Belafonte found his way to Piscator: he had to find his way to the theatre, and My Song gives an inspiring account of the first play he had ever attended.

The end of his wartime duty at age nineteen had freed him from the anxieties of lethal accidents in handling munitions and also the devastating racism in the military, but it had left him in a deep funk with a sense of dislocation and a lack of funds. As he was working as a janitor’s assistant for his new stepfather in Harlem, a tenant in one of the buildings offered him a ticket to a play in which she and her boyfriend were acting, at the American Negro Theatre (ANT). Quiet as the Catholic church to which his mother had dragged him each Sunday morning before they made tracks to the clamoring Apollo in the afternoons, this theatre stunned the young veteran. When the curtain rose, the poise and confidence of the actors “radiated a power that felt spiritual.” On the stage was Home Is the Hunter, an original play about black servicemen trying to launch their lives in Harlem after the war. This was his world, but also a whole new world, and it mesmerized him. It left him absolutely transfixed.

“As a friend, he was bedrock loyal… What shocked me was all the stories he’d taken with him to his grave… not just of Broadway and Hollywood but of the civil rights movement, all his passionate efforts on behalf of blacks and Native Americans….” — Harry Belafonte about Marlon Brando, My Song.

The ANT, started in 1940 in the basement of a Harlem public library called the Schomburg, had followed the guidelines of W.E.B. Du Bois to create plays by, for, about, and near black audiences so as to speak to their lives and visions. Belafonte attended regularly and got to know the group. Soon he was invited to join them as an actor, and his first lead role, in the summer of 1946, was as a young Irish radical in Juno and the Paycock by Sean O’Casey. Paul Robeson, a good friend of O’Casey, had come to see what ANT would do with a challenging play written by a white dramatist about white characters. He was impressed that the group had branched out and taken on social issues relevant to all. And Belafonte, in his first meeting with this giant, was impressed with the love and the sense of responsibility that emanated from Robeson. The man’s soulful basso-profundo singing of spirituals and folk songs, his landmark acting of all the black leading roles, and his record of speaking out for justice around the world led the young protégé to observe, “There could be no higher platform than the one to which he’d ascended.” Belafonte had found the role model for his life.

He had also met his first real friend at the ANT, fellow West Indian actor Sidney Poitier. Not only would their careers dovetail with each other’s, with amazing parallels and coincidences, but at times they would collide in ways unacceptable to Belafonte, generally over politics, both in relation to civil rights and to Hollywood. Still, Belafonte rallied Poitier to his side in some of his most dangerous and dauntless moments. One major difference, among others, was that Poitier couldn’t sing.

Harry Belafonte, a devoted fan at The Royal Roost, became fast friends with the musicians there and worked himself into his first actual singing gig — with a “back-up” band of Charlie Parker, Max Roach, Al Haig and Tommy Potter, no less. He was on his way to becoming a jazz singer of pop songs to swoon over, but in that capacity he didn’t feel right in his own skin. Instead, galvanized by Pete Seeger and his People’s Songs movement, not to mention Woody Guthrie and Huddie Ledbetter whose songs he’d sung in his breakthrough at the Dramatic Workshop, Of Mice and Men, off he went to the Library of Congress to comb through the volumes of folk songs collected by Alan Lomax. Belafonte chose a global repertory — American, English, Haitian, Irish — to perform at the Village Vanguard in 1951 when it was still a house of folk music. It was there that Robeson appeared for a second significant time on Belafonte’s backstage turf. This time, congratulating him, he told the young vocalist,

You’re on a big path. Get them to sing your song,

and they’ll want to know who you are.

My Song continues, through some 460 pages, to tell Harry Belafonte’s story as well as any book could, intimately, deeply, expressing the author’s cogitation of his own life in the context of all those others, far and wide, that allowed him (and challenged him) to make that life meaningful, but it is at this moment in his career that a film can add multiple dimensions to the expression. Few photographs were taken of the young Harry Belafonte: for one thing, neither of his parents was a legal immigrant until each re-married, and for another thing, Harry and his mother “passed” for some time to obtain better housing in New York, so the boy lived a rather underground life there. In his Jamaica milieu, cameras were scarce. Yet as a young man he began to make headlines as a singer, and publicity photos as well as live footage soon followed. As a vocalist he was an absolute stylist — he had a compelling a cappella voice with a flexible range, a well-rounded international repertoire, and finesse with accents, dialects, and languages. Arriving along with the natural gift of his creamy tenor vocals was his smile that spoke a personal identification with and investment in every song he sang. He used that integrity to act, on the stage and the screen but at the same time on the podium, at the negotiating table, and in the front line.

Just after Three

for Tonight with Marge and Gower Champion in 1954, a local black newspaper

editor told Belafonte, “You sure made history in Richmond tonight…. You danced with a white woman, and held her

hand in a segregated house — and nothing happened.” — Harry Belafonte, My Song

Sing Your Song

Sing Your Song is a wonderfully archived treasure house of those political moments, turning points not only in Belafonte’s career but in world struggles for social justice. And again, just how indivisible these bold strides are attests to the moral and artistic integrity of the man and the organic unity with which he has conducted his life. The extended bildungsroman that shapes sixty years of committed activism in My Song is condensed into 104 minutes in the film, Sing Your Song, but more than that, the documentary shifts gears in tone and purpose. Not strictly a bio-pic (nor even a bio-doc), it’s made in the tenor of an advocacy film — a call to action — and its scale is epic. Belafonte narrates, almost griot-style, especially given that much of the film is actually sung and dramatized, through performance clips and old footage. Interviews, eye-witness accounts, and excerpts from FBI files are also part of the seventy hours of material distilled into less than two.

This recent history is, sadly, often unknown to young generations and new immigrants, but for those who have lived through it in this country, the feeling is hardly nostalgia. The density of the material can seem overwhelming, not because it isn’t familiar, but because maybe few of us have seen it all put together this way before. If the book goes behind the scenes, the film shines the klieg lights on what so many Americans took for granted — that the races were not to mix, that class and color lines were not to be crossed — all the while we keep seeing it happen. Step by step, we see Belafonte not only fighting these codes, but changing them, if not on the stage or the screen, then in his own life.

What brings immense pleasure in the film is director Susanne Rostock’s intelligently graceful editing with Jason L. Pollard, through which the wit of the songs is played for theatrical impact or irony against the moment on the screen, be it personally or publicly political. Songs of sorrow, work, and joy, sometimes plaintive, other times rambunctious, often pack a soulful protest in their pithy patois, their punch lines, or the nuances of double entendres. Global folk songs or spirituals that they are, their content and meaning can almost always be traced to the particulars of Belafonte’s individual life. In the Nat King Cole Show on television, Belafonte playfully sings, “I wonder why nobody don’t like me — or is it the fact that I’m ugly?” as he begins the song “Mama Look a Boo Boo”; he first heard it in Grenada while filming An Island in the Sun with all its attendant racial restrictions, but it can just as easily be applied to his own childhood relation with his Jamaican father. The voice is that of a disgruntled dad in dialogue with his two boys and their mom. And according to some of Belafonte’s own four children from two marriages (each child appearing in Sing Your Song), he wasn’t always the perfect father, either. Nonetheless he remarks that many of his songs in the early years were directed at his own children, “Scarlet Ribbons” perhaps the best example. We hear it sung to a montage of home movies in which the girls, Adrienne and Shari, push their dad in a stroller as he rides, crunched up, holding a camera on his lap.

“Banana Boat Song” (“Day-O”) is of course a memory of his own childhood, however poignantly symbolic it may be of universal strife. “Sylvie” conjures the shackles image that recurs too many times in Belafonte’s life as he sees his close and esteemed friends — Martin Luther King, Jr. and W.E.B. Du Bois, for example — both shackled in his lifetime, the frail octogenarian Du Bois literally chained as well, and King sentenced to a chain gang, and then most recently, a five-year-old girl in Florida, hands tied and ankles cuffed together by police who haul her off for being “unruly” in kindergarten. Several song performances resonate with the need for social change. On Tonight with Belafonte, special guest Odetta sings a duet with the host, “A Hole in the Bucket,” with a wry irony circling through the lines that suggests the systemic flaws of the nation. “Jump in the Line” becomes more than a vibrant dance song from Trinidad’s carnival tradition when Belafonte sings it in a Calypso medley on The Smothers Brothers television show against a backdrop of the riots and the convention of Chicago in 1968. CBS cuts the entire segment, replaces it with a Nixon commercial, and “Sure enough — boom!” comments Tommy Smothers, “We weren’t just canceled, we were fired.”

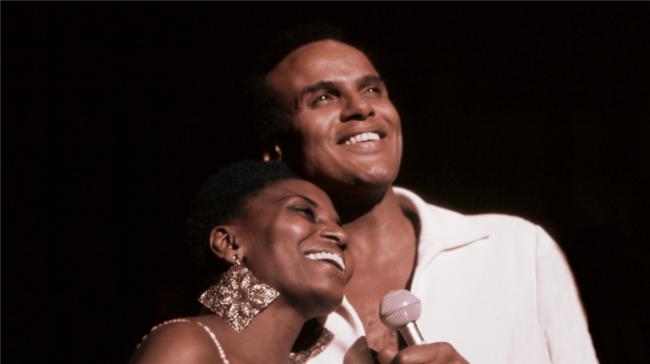

Miriam Makeba says in Sing Your Song: “Belafonte means a lot to people, struggling people around the world, because he took all our struggles and made them his own.”

Sharing the Cocoanut

The film works at once as a primer of the American civil rights era through a key player’s point of view and as a raconteur’s inner-circle revelation — another dimension entirely — of a history many of us thought we knew.

Harassment and even mortal threats are either hot on Harry’s heels or waiting around a corner for him through much of the film, in the form of fabricated FBI files stemming from his association with the blacklisted Robeson, threats from the Ku Klux Klan during his singing tours and his SCLC and SNCC work, and proclamations from the Las Vegas mafia that he will either honor his night club contract (despite being housed in the ghetto slums) or leave the city “in a box.” Samuel Solomonick (alias “Jay Richard Kennedy”) enters the story intermittently and by surprise by signing on as Belafonte’s manager while his wife entices Belafonte into therapy; their tandem gig ultimately rears its ugly head with Solomonick shored up as a turncoat — from Soviet agent to FBI informer — partnering with his infiltrator wife and then making new mischief as a talk show host bringing Martin Luther King to his panel of “guests.”

The problem Belafonte poses for these agents of menace is nearly always the same: he refuses to refrain from integrating the races and classes — on the New York stage, on singing tours, in Hollywood, on network television, in Las Vegas hotels and hot spots, and in the South. Fran Scott tells the camera how in 1952 in a Jim Crow Las Vegas, Belafonte integrated the Thunderbird: “Come on, we’re going swimming, he announced at my door in his robe with a towel over his shoulder.” She followed him to the pool where he did an ostentatious dive into the water in front of all the hotel’s white guests, only to be begged to pose for pictures with them a moment later. “He could have been shot,” she observes, but that was Harry.

In a 1968 duet with Petula Clark for her first TV special, she and Belafonte are singing an anti-war anthem and she puts her hand on his arm in a stroke of solidarity that sends the Chrysler advertising manager into panic. Yet when he calls for a re-shoot without the gesture, she and her husband, the producer, refuse, regardless of how the decision might jeopardize her career. The manager cows to them when word gets out, and he meagerly apologizes. But this leverage has been hard won; earlier natural and spontaneous body language has been rigidly prohibited, to the detriment of artistic integrity and box office success alike.

Belafonte’s on-screen attraction to co-stars Joan Fontaine in 20th Century-Fox’s 1956 Island in the Sun and Inger Stevens in MGM’s 1959 The World, the Flesh and the Devil posed too much of a threat in the producers’ eyes, and we see clips from films that have been hacked up beyond recognition, in which Belafonte claims the natural chemistry (as called for in the scripts) has been “neutered.” He and Fontaine work out a way around it by sharing sips from the same coconut in a very precise way, but we realize this censorship contradicts Belafonte’s own real life, in particular his 47-year marriage to Julie Robinson, a lead in the Katherine Dunham Dance Company. A mesmerizing scene of them dancing together, slow-motion, to Belafonte’s voice on the soundtrack singing, “And I Loved You So” convinces anyone that Marlon Brando did well when he introduced them on a movie set because he himself was pre-occupied. The lyrical scene, demonstrative of love as innately human, goes a long way as a counterpoint to all the anguish suffered at the hands of xenophobic film and TV moguls and their corporate accomplices upholding hollow Jim Crow codes.

“Different voices, but a shared humanity: this was my platform, my authenticity, my politics,” says Harry Belafonte in My Song. The New York 19 installment of Tonight with Belafonte won an Emmy, the first ever awarded to a black television producer.

Speaking Truth to Power

Harry Belafonte stands up to racial bigotry in 1956 by forming his own company, Belafonte Enterprises, Inc., or BEI, with one subsidiary for music publishing (possibly the first all-black company), one for film projects (HarBel Productions), one for concert tours, and one for backing Broadway plays, including Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. The self-publishing of his songs along with Lord Burgess (Irving Louis Burgie) and Bill Attaway begins with Calypso, which calls up a series of “firsts” that can be traced through both Sing Your Song and My Song.

The film makes several of them visually explicit when Steve Allen, the genteel host of one of the most artistic TV variety shows of the era, presents Belafonte with three tangible golden records in a row, one for “The first performer to sell over a million copies of a single album” (RCA’s Calypso); another for “The first artist ever to have sold a million copies of a record in England” (Calypso); and another for “Selling a million copies of ‘Day-O’ itself.” In this scene he then goes on to sing “Cocoanut Woman” on the Steve Allen Show that night; in his book he points out that from that moment on, he would be very intent on broadening his repertory beyond Calypso music.

A few years earlier in 1953, Belafonte had already earned a Tony Award for his first appearance on Broadway, in John Murray Anderson’s Almanac. In 1954 he went on to play his first male lead in a film, Carmen Jones, based on Bizet’s opera, Carmen, and we see clips of the first all-black musical produced by a major Hollywood studio (including the lip-synched voice of LeVern Hutcherson and excluding that of Marilyn Horne), which leads to Dorothy Dandridge becoming the first black female to be nominated for the Best Actress Academy Award. By the end of 1959 Belafonte wins the first Emmy ever awarded to a black television producer for Tonight with Belafonte, directed by Norman Jewison for CBS. Revlon, the sponsor, is thrilled and orders five more shows, so he dives into the project and creates the next, which he refers to as “The Great American Mosaic.” He begins close to home. All in one postal zone in NYC (number 19), he finds “most of the world’s musical styles and cultures, from classical in Carnegie Hall to show tunes on Broadway to bebop on Fifty-second Street, but also salsa in Latin bars, jigs in Irish joints, the music of Israel in synagogues and the Yiddish recitals in theaters…” Highlighting each genre and culture within that tiny but densely populated district, a montage of performances in the film shows us New York 19; the ratings are excellent and the critics rave, but to appease southern racists who won’t tolerate whites and blacks singing and dancing on the same stage, Charlie Revson wants Belafonte to create a show with black performers only.

In the book Belafonte’s response to Revson is, “when you tell me no whites, you’ve crossed a line: morally, socially, and politically. There’s no way to square it. I cannot become resegregated.” Narrating the film, Belafonte recalls, “The whole world was experiencing a new consciousness. I could not acquiesce. I would not change the format. And I left.” On the air, he tells his viewers, “Thank you for being with us. See you around…” He smiles, tosses his suit coat over his shoulder, turns around and walks off alone to the back of the empty stage. Privately, when he later reflects off-stage, the “epiphany” comes: he was fighting to change Hollywood, and then television, to cast black actors in dignified, substantive roles,

to have black leading men who did all the things that white leading men did — chase villains and rope horses, make money and make love — with leading ladies black and white. Time and again I’d failed. My epiphany was simple. The movies and television weren’t all-powerful arbiters of culture. They just reflected the culture. Doing battle with them was like fighting a mirror.

To change the culture, you had to change the country.

And only one thing would change the country: the movement.

In a Harry Belafonte commercial for John F. Kennedy, Belafonte talks about his own participation in the upcoming presidential elections and urges voters to support JFK.

“Our Task Is to Find His Moral Center”

While Belafonte’s leverage as an entertainment celebrity is certainly evident, it is due to his increasing involvement in the civil rights movement that we see his counsel, support, endorsement, and private negotiations continuously sought by the Kennedy brothers during JFK’s Presidential campaign. When as a result of a traffic violation, Martin Luther King ends up in solitary confinement in a maximum security prison, the Kennedys “wrestle with his arrest,” we’re told, until John considers the crisis as central to the Democratic Party vote and Bobby, affronted by the abuse of justice, negotiates with the state of Georgia for King’s release. It’s one of countless times that private conversations will be conducted between the candidate, the President-elect, and the Attorney General on the one hand and King, other movement leaders, and Southerners in seats of power on the other hand — with Harry Belafonte as the mediator and often the contributor or conductor of funds.

Trust is always an issue, as is the question of just how much a Kennedy in the White House will do to fight poverty. We see Belafonte host the Tonight Show in 1961 with Bobby Kennedy as a guest, the same man who’d been an attorney for HUAC and submitted an arbitrary list of perceived “communists,” including key people in the movement. But King articulates his own on-going modus operandi regarding Bobby: “Somewhere in this man sits good. Our task is to find his moral center.” It’s Bobby Kennedy’s visit to the South to meet first-hand the people living in poverty that Bobby discusses on the Tonight Show, speaking clearly and purely from the heart, even while he coyly dodges the question of whether he will pursue the Presidency.

A trip to Greenwood, Mississippi in 1964 during “Freedom Summer” is a poignant moment in history and memory. Harry Belafonte not only raised $70,000, literally overnight, to support youths both black and white who were risking their lives to register black voters, but he personally delivered it. My Song opens with the account as a dramatic first chapter that then flashes back to the beginning of Belafonte’s story. In the film, Sidney Poitier, solicited as Belafonte’s sidekick for the trip, jokes about it now, relaying exactly how it was no joke then. John Lewis, Congressman and Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee member, testifies as to what happened from the point of view of those already on the scene, planning how to dodge the Klan:

Harry, he stayed in this house with a family in the Delta. That was so-o-o dangerous. The house had been fired on. He wanted to identify, not just with us, but with the local people. And he also wanted to bring us a sense of hope — that “we’re with you” — and I will never, ever forget that.

Belafonte then took thirteen SNCC freedom fighters to Africa with him, to give them a reprieve, as the guests of honor of Guinea’s leader, Ahmed Sékou Touré.

“For all the conversations I’d had with Bobby, and the handful of talks with the President, I never regarded myself as an insider. I never made that presumption. I was a contact, a conduit, a useful character. That was enough for me.” — Harry Belafonte in My Song.

“…Can You Tell Me Where He’s Gone?”

There are several scenes in Sing Your Song in which Belafonte demonstrates his resistance to making gestures and appearances that he finds objectionable. One is the invitation to attend Nelson Mandela’s inauguration as President of South Africa after Mandela has endured a grueling twenty-seven-and-a-half years in prison, in large part on Robben Island. With Miriam Makeba and others, Belafonte has fought against apartheid, but now he refuses the invitation to such a joyous occasion because of the tragic events of the moment in Haiti and President Clinton’s treatment of the exiled President Aristide. Yet soon enough, in 1990, we see Belafonte shouldering the sole responsibility of designing and managing the complete 8-city, 12-day itinerary for Nelson Mandela and personally escorting him and his wife throughout the African’s first visit to the U.S. “Harry, my boy!” Mandela shouts to greet him as he deplanes, recognizing him in the crowd though the two haven’t yet met face to face. Over the next adventurous days, how could Belafonte not recall those days of assassinations of his other close political friends!

Another occasion on which Belafonte refuses to participate is, ironically, Martin Luther King’s first birthday after his death. Coretta Scott King invites a wide and eclectic assortment of guests for a lavish dinner, including Henry Ford II, who has just negotiated one of the most brutal labor contracts ever with South Africa’s apartheid government, while the ANC, supported by the SCLC, has just called for sanctions against such companies. Belafonte declines his invitation to the dinner.

Perhaps the most moving sequence in the film works because it is both familiar and unfamiliar at once. It opens the space between black screens for a mixture of emotions — deep sorrow, respect, empathy, solidarity, and love — that are difficult to shake off after the film ends. It all starts with Belafonte, hosting the Tonight Show, pointedly asking Martin Luther King, a guest there, if he fears for his life. King, in his rich, deep southern drawl, remarks famously about the difference between how long and how well a life is lived, and as the screen fades to black, Bobby Kennedy’s crisp, cracking voice announces King’s death, fading in to a screen once again black but for a spotlight on Bobby’s face in the crowd (after all, he would be the next to go). From Belafonte’s speech in Memphis four days later, at a sanitation workers’ strike where he pays tribute to his “departed brother,” the black screen returns, accompanied this time by Belafonte’s voice-over, almost a year later, piercing the silence in song: “Has anybody here…seen my old friend, Martin? Can you tell me where he’s gone?” The scene is Riker’s Island Correctional Facility in New York City, a prison overflowing with black youths. It’s an eerie feeling because as he sings, the white light shining through the grid of the many prison windows up high, shot from a low angle, brings to mind a church and even the heavens above. At the front he continues, “He’d freed a lot of people, but the good, it seems they die young — I just looked around and he’s gone.” Is it the spotlight that forces Belafonte’s eyes closed? It also makes a shadow on the red curtain behind him. The bodies of the inmates turn to silhouettes, and the frame fades to black once again.

Harry Belafonte sings the blues with inmates at a Los Angeles jail.

What Do You do Now?

Striving to launch the Poor People’s Campaign that King had in mind when he died, Belafonte extends its scope (as King had intended) to anti-nuclear rallies in Bonn, to Native American resistance in Toronto and the U.S., to starvation prevention in Ethiopia and Sudan, to intervention against gang violence in Los Angeles, and to the idea of Gathering for Justice throughout the country, exchanges between the “elders” and the young that might yet allow an effective “passing of the baton” from the last generation to the next. Ultimately, Sing Your Song leaves us with its opening question, “What do you do now?”

Sing Your Song is not only a crash course in the social and cultural history of the last half-century, it is a clarion call to action. Its soundtrack of the full songs introduced in the film catches almost anyone in its rhythms and rhymes, its pesky lyrics and soulful sounds. As Harry Belafonte would have it, from the film to the book to the songs, any one of us might just “jump in the line….”