5-3-13

Nelson Pereira dos Santos and the Popular Art of Cinema

By Diane Sippl

From April 20 to May 12, 2013, the UCLA Film and Television Archive, along with the UCLA Latin American Institute, the UCLA Center for Brazilian Studies, and the Consulate General of Brazil in Los Angeles, is offering a seven-film retrospective, “Cinema According to Nelson Pereira dos Santos,” hosting an in-person visit from Brazil’s quintessential filmmaker for post-screening discussions on Saturday, April 20 at 7:30 pm and Sunday, April 21 at 7:00 pm. at the Billy Wilder Theater (tickets: www.cinema.ucla.edu).

Perhaps no other country has experienced filmmaking quite like that of Cinema Novo in Brazil, and no other filmmaker embodies its evolution as well as the prolific Nelson Pereira dos Santos. By 1963 his Vidas secas (Barren Lives) marked the high point of the first phase of Cinema Novo, a movement of politically engaged Brazilian filmmaking that would influence countless cineastes across the world for decades to come. By taking the camera to the streets and hillsides and fields to film people who were playing roles akin to themselves, this populist cinema brought the lives of Brazil’s urban poor and its migrant laborers to the screen with fidelity and dignity and then, over the next decades, also presented the country’s marginalized indigenous and African traditions, its colonial history and political repression, and its singularly celebrated arts and letters.

Cinema Novo began with Italian neorealism, which emerged with, and largely as a result of, World War II and succeeded in re-defining cinema in Italy, Europe, and eventually many places in the world. One of those places was Brazil, which had developed its own film industry since the earliest days of silent cinema, but one modeled on the production goals and methods of the Hollywood studio system. Yet the concept of filmmaking that impressed Nelson Pereira dos Santos was the one he discovered in Europe when he met Cesare Zavattini, one of the architects and key players of Italian neorealism. This new stance and vision was a major inspiration and shaping force for Dos Santos in making his early films, beginning with his exhilarating Rio, 100 Degrees (Rio, 40 graus) in 1955. Glauber Rocha, who would soon come to join Dos Santos in launching Cinema Novo, later described this film as “revolutionary in and for Brazilian cinema” and as “the first really committed Brazilian film.”

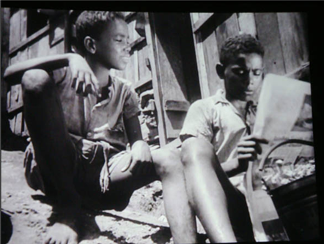

Rio, 100 Degrees (Rio, 40 graus), 1955

In the interest of forming an autonomous and genuinely national cinema for Brazil, Dos Santos conceived of Cinema Novo as a group of auteurs whose cultural politics emerged as a collective practice. Each director employed his own principles and methods of filmmaking, with a freedom of subject matter and means of expression that led to his own aesthetic. In fact, in his long career, Dos Santos has worked across numerous genres, spanning the historical novel, political satire, ethnographic inquiry, the prison diary, urban mythology, the music film, and others.

Nonetheless he has always aspired to apply his convictions and aesthetics as an auteur to creating a populist cinema that embraces the lives of his fellow Brazilians. That said, it’s a contagious cinema, perhaps nowhere more easily felt than in his latest opus, which leaves many a filmgoer, far and wide, humming all the way home.

The following two-part interview

is a transcribed and edited version of the discussions between the preeminent

filmmaker, Nelson Pereira dos Santos and the preeminent historian and scholar

of Brazilian cinema, Randal Johnson, Chair, UCLA Dept. of Spanish and

Portuguese, following the screenings of the first of Dos Santos’ films, Rio, 100 Degrees (1956) and then the

most recent, Music According to Tom Jobim

(2012). The audience joins in near the

end of each conversation.

Rio, 100 Degrees

“My biggest contact was with Zavattini: I gave him an ear, and he gave me a voice.”

Nelson Pereira dos Santos

Q This film is a cross-section of Rio with its many different locations and characters of the city. How did you decide to make it?

A To be honest, to make a film with diverse places and things happening was born in reading James Joyce. I’d just finished reading him in Spanish because he wasn’t translated into Portuguese yet. The city of Rio is very rich, so I thought of making the film as one day with many things happening at once. Of course the subject matter of the film is very different from that of James Joyce, but the structure of the film was the first step.

Q How did you cast the child actors who sell peanuts? And how did you choose the music?

A In the first place, I had contact with people who lived in that favela, with Zé Keti, the man who’s always with the boy, Miro. At that time Zé Keti was just beginning his career as a composer. “Oh So Samba,” the song, was a great hit then and Zé Keti was big in the samba schools. So he chose the boys who would be the actors through an announcement in the samba school. We did try-outs, and in the end, we chose those five boys. One — the one who goes up to the cable cars to escape the man stalking him — went on to do so many films and many (tele)novelas. Choosing “Eu Sou o Samba” worked as a synthesis. Some of the other actors were already known in theatre and others were from musical theatre. Yet many in the film had not worked as professional actors.

Q For the Copacabana scenes, what were the challenges of shooting on location? Did you have a plan to shoot all over the city?

A First, my team was very small. The DP was operating the camera, always hand-held. There was no tripod. There was an assistant with me, and other collaborators who were not professionals in the field who helped the people who were the public to be comfortable and not look into the camera. So it was a sort of contraband or pirate kind of shooting in which actors would get directions as the camera would roll.

Nelso Pereira dos Santos

Many of our friends were in

the football scenes; we took up a tiny space of the football stadium, which

was full.

The music director who orchestrated it was Radamés Gnatalli. The melody is the same as the samba. The music director composed an erudite piece using elements from the samba. He’s a modern composer of many symphonies and is very learned. For many years he also worked to make a living by arranging music for radio and television.

Q How did you conceive of representing the favela in the film, compared to the representation in City of God, for example?

A At the time there was less violence. The population of Rio was two million; in the favela, 200,000. When violence did happen in the favela, it was normally domestic violence, problems with love and fidelity. Of course there were delinquents, illegal occurrences, criminal acts….

Q Did you visit the favelas before making the film?

A Yes, with my friend; in thinking about the script and planning the film, he was with me all the way. It was also in my head to get rid of the prejudice and the mentality of the middle class regarding the favelas. “Delinquent” for them meant someone who lived in the favelas; the term was synonymous with a favela dweller. It’s common to apply negatives to social groups. The film shows that they live there because they don’t have money to live in the Copacabana, but the family morals are still there. Films today address the violence that is there, but back then, drugs, alcohol, marijuana were like remedies. People weren’t smoking to get high; it was just normal.

Q Black Orpheus is a French film that was made just a few years later than Rio, 100 Degrees. People are just singing and laughing in Black Orpheus. It’s a real disservice to them, much as City of God is with its total violence. Here we see youths kicked out — of the stadium, the zoo — brutalized and marginalized. Your film is so much more complex.

A The organization of power in the favela is very different from the organization outside. The leader of the favela was always important, even if we didn’t know why. His word was law. Every day in the newspaper there would be a story about criminals or thieves in the favelas.

Q How did you manage the camera movement?

A There was always someone with the photographer to prepare for the scene. The movement was marked, but without a camera. People thought it strange to see a guy with big binoculars going around, but he was less conspicuous than a big camera.

Q Did you use any special lighting?

A We used filters — a yellow one that filtered out fifty percent of the light.

Q The film’s ending brings a unity of culture and social class: a shared celebration of samba and a bonding that comes from the strike that the two rival men remember together.

A Speaking of the ending, lots of my friends were telling me to have the two guys fight, and to let it become a really big fight for the end. Here you see that the poor can live very well with their own rhythm and there’s a happy ending for each story. The soccer players play well and the two rivals for the woman work out their differences because of their past. The only one who doesn’t end happily is the boy who dies at the Copacabana. But they all have their own paths.

Q The ending is optimistic. Your film isn’t pessimistic like the films of Buñuel — for example, Los Olvidados — or like City of God. How does your film relate to these?

A The truth is, with Rio 100 Degrees I was greatly influenced by Italian film at that time. In Brazil they were making films then in studios. When the film companies were starting out, the big concern was, ‘Where will we put the studio?’ Not ‘What film will we make?’

Italian cinema suggested that one could film in the street, with real people and real places, not celebrities and stars. Glauber Rocha coined the saying, ‘A camera in the hand and an idea in the head.’

Los Olvidados got to Brazil after neo-realism, but it influenced another generation. The films that came to Brazil after the fall of Mussolini were The Bicycle Thief, Rome Open City, and the works of Pietro Germi.

Rio, 100 Degrees (Rio, 40 graus), 1955

Q Had you actually contacted the neorealist filmmakers?

A Yes. This film was shown at a big festival in Paris in 1956. I participated in a congress that defended freedom of expression. Also attending this conference was a man named Cesare Zavattini. He sat next to me and we talked and exchanged ideas. Every time I went to Italy I looked him up. I met others when they came to Brazil, but my biggest contact was with Zavattini: I gave him an ear, and he gave me a voice, content.

Q You were one of the first filmmakers to show films of the favelas. What was the reaction?

A Columbia Pictures liked the film a lot and bought it. But Brazil banned it. It was the beginning of the end of democracy there. Then there was a campaign to release the film, and it worked. It was banned because the Chief of Police said ‘It never gets that hot in Rio — only 36 degrees’ (or 99 degrees Fahrenheit). They said that the film showed only misery and poverty and that it was a destructive view of Brazil. And it was made by Communists.

Columbia Pictures helped to support the film, as did others. So it did have a mixed legacy and influence — and it set the stage for Cinema Novo.

Q What was the future of Cinema Novo after your film, and especially the more radical films of Glauber Rocha?

A Of course I have a great admiration for Glauber Rocha, and early on we worked together, on our first feature, The Turning Wind. I edited it. After that, we were always together. Our films were revolutionary and allegorical. The films had more of a cult reception. Success is relative, and it wasn’t the same success as in another genre, porno chanchadas; but Glauber’s films are alive today, while the other “successes” are now forgotten.

Q For many years you were a film professor at the Federal Fluminense University, across from Rio, and he used his students to make his films, so you was a mentor. How can film change the culture? Is it better now? How?

A Things are better. Things have grown. Films that reflect reality are now accepted and are shown in theaters and homes, so that’s much better than it used to be. This film (Rio, 100 Degrees) is fifty years old today, and the films made by young people now are thematically very different from this one. Now there’s a lot of film production coming out of Pernambuco, but it used to be Rio and São Paolo.

The industry produced more than ninety feature-length films last year, mostly fiction but a good number of documentaries. Brazilian cinema today is thematically diverse, pluralistic.

And I still feel the presence of what Cinema Novo was. It represented modernism, in literature, art, music, and in film. Modernism had already arrived in Brazil in literature and the other arts, but cinema was still imitative of American films. After Cinema Novo, there were thirty or forty directors, but not a film school, and the books they read were in French or Spanish or English, but not Portuguese.

Now there are many university

film schools, and independent film schools as well. There are many books in Brazil,

both theoretical and practical, written about filmmakers. So cinema Novo had an influence. But now

there is great diversity as well. We

thank those who’ve written on Cinema Novo.

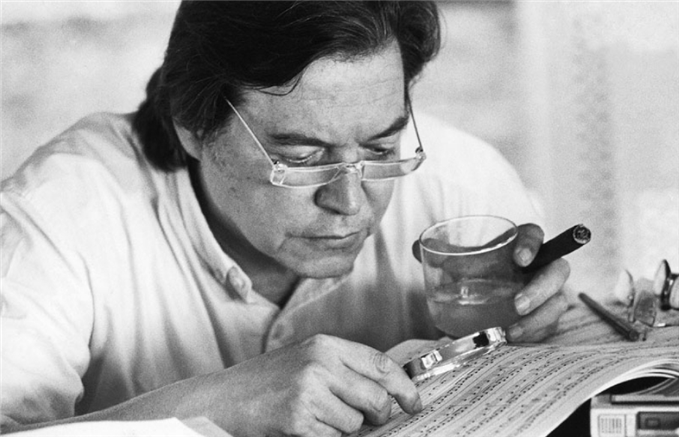

Antônio Carlos “Tom” Jobim

Music According to Tom Jobim

“The way it is, spectators each have their own stories of Tom Jobim in their hearts.”

Nelson Preira dos Santos

Q Tom Jobim was a master of Brazilian music, and we’ve just seen him presented by a master of Brazilian cinema, Nelson Pereira dos Santos. The film is chronological in following Tom Jobim’s life. Beginning in the 1950s, Tom Jobim and Gilberto Gil were changing the face of Brazilian music, and Nelson Pereira dos Santos and Glauber Rocha were changing the face of Brazilian cinema. How did these two arts come together?

A Bossa Nova came first. In the film, Tom Jobim says it was João Gilberto who first used the expression. At the time there was always the possibility of meeting music people, especially in the bars of Ipanema. And Jobim wrote lots of music for the cinema, for Andrae in Cinema Novo. I met Jobim, but I didn’t work with him until 1984, in a program for TV by the same title as this film, The Music of Tom Jobim. It was four hours long, and we recorded it in Tom’s house, receiving major figures of pop music in Brazil. Through the conversations with Tom’s visitors, the public was able to see the evolution of Brazilian music from the beginning of the 20th century. Tom’s knowledge was fantastic, not only regarding Brazil at the time, but also considering the lyrics and songs he knew — Radamés Gnatalli, who scored last night’s film, Dorival Caymmi, Chico Buarque....

Q The film we’ve seen tonight is an unusual documentary, using no words, no voice-over, no inter-titles. “Music is sufficient,” as it says at the end of the film. How did the work go for you?

A I had lots of trouble, because the producer and others were used to talking heads and labels identifying whoever’s on the screen. The first version was exactly this one, allowing the spectators to choose what they’d like to focus on. We also had the idea of forcing the spectators to ask questions: Who are these people? Where did I hear this music before? We wanted to explore these possibilities.

I had the experience of people

coming to me saying that the sequence in Vienna

made them cry, as well as another with Chico Buarque. The way it is, spectators each have their own

stories of Tom Jobim in their hearts.

Q You must have had hundreds of choices — how did you choose these songs and interpreters?

A The primary advisor in this effort was Tom Jobim’s son, Paolo. Once the music was gathered, Paolo did the first analysis to see if the quality of the material was sufficient. Some, mostly what came from Brazilian TV, had problems with its quality and also with the specificity of each interpreter. Sometimes we had to accept scratches on the track because it was the only footage available from that singer, but these suggested the idea of the period. TV used 16mm footage.

Q One person is absent from the film — Joãn Gilberto. Why?

A They did register Gilberto’s importance in the film, but Gilberto is making his own film, so he didn’t want to give us the rights to his songs. We wanted a wonderful scene with Gilberto and his daughters, but it wasn’t possible.

Q There is one moment of silence in the film, a memorial of Tom Jobim’s death in 1994 with Caetano Veloso and others.

A That show was an homage to Jobim that took place not long after his death. That moment marks a shift in my film: it’s no longer a documentary but an homage. Then to cut from Tom at Carnegie Hall to the Carnival scene with Tom, with the audiences applauding, is a nice way to end the film. There are always scenes of audiences applauding, around the world.

Q You made another documentary, A Luz do Tom (The Light of Tom).

A In Rio, it’s already released. It uses Tom’s sister and his first and second wives — three women. They talk about how he worked, how he created his music, and his personality as he wrote. A counterpoint in the film is Tom playing at the piano. He doesn’t appear — just his image. It’s very difficult to do subtitles with films like that, with lots of spoken language. When people speak, they improvise, and that makes it difficult to capture what they say in subtitles. It’s possible, but it’s harder than it is with dialogue in fiction films.

Q Why “Tom” Jobim? Is it a nickname? Are they two different people, Tom and Antônio Carlos?

A It’s a lot easier to say “Tom.”

Q The Judy Garland sequence was the first mystical moment for me. Was the “blur” to make it more mystical, or was it the only footage available?

A That image was criticized by the New York Times as being old and ugly. She performed that song when she was a bit older than the image she would have liked to project, so the blurring was done to hide some wrinkles. It was the most expensive sequence in the film.

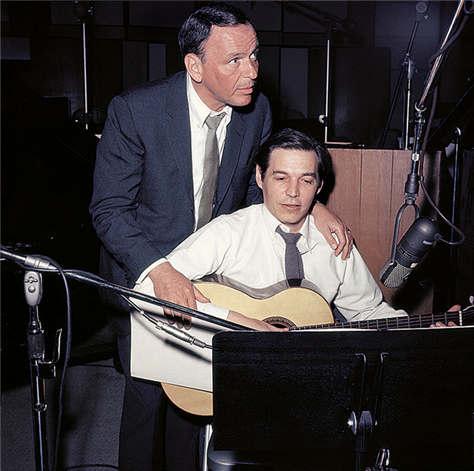

Music According to Tom Jobim

Q How long has jazz been in Brazil, and how did it get there?

A It came with the inauguration of radio in Brazil. Before that, if you wanted to hear jazz, you had to travel.

Q What was the most surprising thing you learned about Tom in making this film, since you were already contemporaries?

A Doing research for the film with Tom’s granddaughter and at the Tom Jobim Institute for the foreign material, I was surprised by how much material was available. So how to choose the best? For example, we found a performance of Gilberto Gil and Stevie Wonder, but it was amateurish, and the quality wasn’t sufficient for our film.

Q I’d like to see the film again, but without the music, because there’s also a separate melody going on in the film — all the faces and close-ups of the people involved. And they made me wonder: why no Spanish material?

A There was not much available, and it was not of high quality. I’m sad about that.

Q This romance we get with Jobim — is it something very Brazilian, or do we get it only with Jobim?

A That’s complicated. I agree, the film does show at times the loneliness of the artist. That’s only Jobim. In the other film I made about him, there’s an image of Tom alone by the lake, and his sister says she’d like to know what was going on in his mind.

The final performance of “Girl from Ipanema” sung by Tom is very different in tone and feeling from those of others who sing it. It says something else. Tom always has a twinkle in his eye, even if other singers look sad. That’s Tom.

Q Why so many French interpreters?

A My first contact with Tom was in France, with the Black Orpheus film, a French film, that won at Cannes.

Music According to Tom Jobim

Q I’m a big fan of Jobim, but an even bigger fan of Dos Santos. How do you constantly renew yourself?

A It’s a bit of work, and a great marriage, with Ivelise, the producer of the film.

Q What other projects do you have?

A I have a film crew ready with a script, but we still need 60% of the money. It’s about emperor Dom Pedro II, the second-to-last emperor in Brazil. It’s more of a psychological film than a historical drama with complicated means. I tell the story in a non-chronological way. Each chapter has its own theme, such as the love between the Emperor and the Contessa, or the war with Paraguay. I selected some of the chapters. I hope to bring it to UCLA next year.