6-17-09

By Diane Sippl

Have you ever been on a boat at

night, looking up at the stars, where the sky and the water become one? You

could be Ishmael on the Pequod with

Captain Ahab, or Huck Finn on a raft with Jim on the

Walking into

As a child Trang Lê experienced

the Vietnam War. In her girlhood she

fled with her family by boat to the most powerful country in the world. She felt blessed to be safe and protected from

remote war zones. She went on to earn two

Bachelor’s degrees, in anthropology and in art, at the

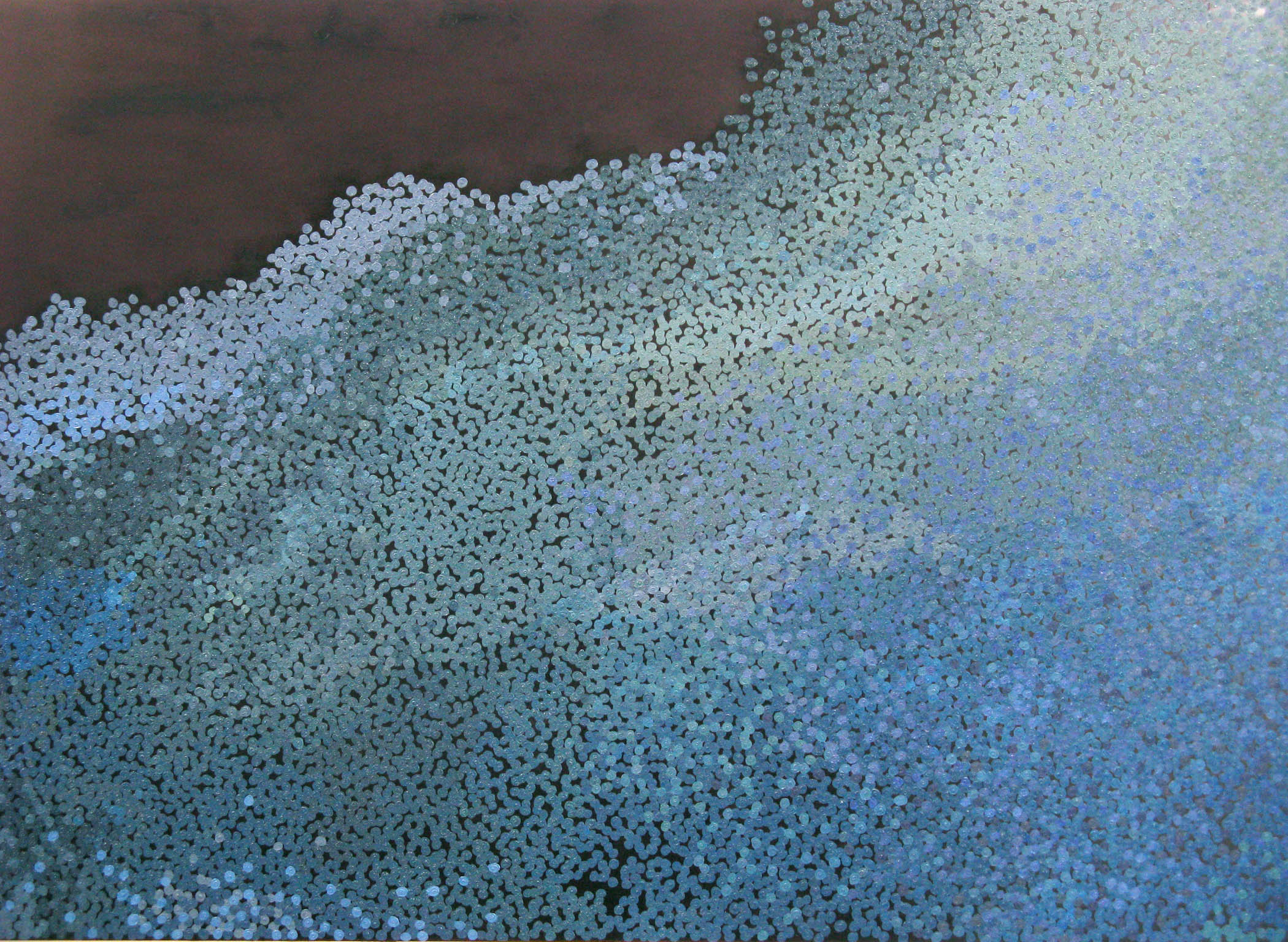

102,477, detail, 2009, oil on canvas and linen, 4 x 48 feet

Her vast, 48-foot-wide painting, 102,477,

references the tally of casualties in the

“I looked at the pictures. I looked at the names. I did it because I needed to. I felt they needed to be recognized somehow. And I wanted to know them. The pictures popped up, and when I saw the faces — that’s when I started to cry. It was very hard for me, so I thought to just make the circle for each, and they added up.”

Making this mark for each deceased person — first American soldiers, then Allies, then Iraqui civilians, then children — has been a healing process.

“The Iraq War brings up my past

and my memories as a child without a voice.

With

102,477, detail, 2009, oil on canvas and linen, 4 x 48 feet

Prior to creating 102,477, Trang Lê

had discovered that painting repetitive spiral circles brought internal comfort and soothing through the circular motion of a small brush. But painting 102,477 was an emotional struggle because it meant facing the topic of war. She explains,

“Counting every circle I made helped me. I had never counted my circles before this project. Slowly, toward the end of the painting, I started to heal and meditation began. And the funny thing is, when I came to the edge of each canvas, I couldn’t cut off the circle. I thought, this is a life — you can’t just cut it off.”

The deaths symbolized in the dots of the painting are palpably arresting; the paint spirals out at you from the canvas each time, from the depth of each separate circle. And as you back away, the work takes a different toll. The myriad marks form an amorphous mass that appears to swell and dissipate with a life of its own. Across the panels, dark spaces take hold, patches of black after a dense build-up.

“I needed a space to breathe, a place to rest,” explains the artist. “When you look into the dark sky, with just nothing, the emptiness helps. Toward the middle of the painting I felt so heavy, so blocked, and that’s when I started to go brighter.”

Have you ever been on the water

at night, floating, so quiet, no sound but the water hitting your boat… the ocean

meeting the sky?

“When we left

Painting

“In their journals, the soldiers wrote about the trees, the environment, and the weather over there, how really hot it was. So I said to myself, ‘Let’s do a willow tree’. I love the movement of the willow, and it’s very seldom that you can find a willow. Then because both the soldiers and the civilians I Googled wrote so much about the heat, I decided to paint the willow red.”

Willow Tree, 2009, oil on linen, 48" x 48"

Mesopotamian Rain, 2009, oil on linen, 60" x 28"

“I don’t want this work to focus

on me, but on people, people in the

“In my last painting, the view is

not realistic for me. I couldn’t do a

search for this kind of landscape in

She meant the hymn, “

“So at the end of my exhibition, I wrap it all up by just saying, this is what it is — dreaming for peace. We all need to dream, for the desire and drive to work hard on peace and make it happen.”

Dreaming for Peace, 2009, oil on linen, 45" x 22"

Ruth Bachofner Gallery

2525

June 6 – July 18, 2009

Photos courtesy of Ruth Bachofner Gallery