3-4-10

Intimacies/Intimismos: Musing with Mary Heebner

By Diane Sippl

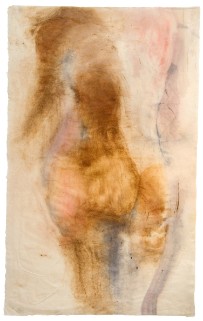

“Thunderhead”

62” x 42”, mixed media on paper

I would like to talk to her, share her secrets, ask her of what difficult clays she was born, from what acts of love and violation she comes.

Eduardo Galeano, Preface, Memory of Fire: Genesis

It is good, at certain hours of the day and night, to look closely at the world of objects at rest. Wheels that have crossed long, dusty distances with their mineral and vegetable burdens, sacks from the coal bins, barrels, and baskets, handles and hafts for the carpenter's tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth, like a text for all troubled lyricists. The used surfaces of things, the wear that the hands give to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things...

In them one sees the confused impurity of the human

condition, the massing of things, the use and disuse of substance, footprints

and fingerprints, the abiding presence of the human engulfing all artifacts,

inside and out.

Pablo Neruda, “Toward an Impure Poetry”

Painting and writing, always the closest two of the sister arts (and in ancient Chinese days, only the blink of an eye seems to have separated them), have each a still closer connection with place than they have with each other; but a difference lies in their respective requirements of it, and even further in the way they use it — the written word being ultimately as different from the pigment as the note of the scale is from the chisel.

Eudora Welty, The Eye of the Story

Tactile Memories, Internal Landscapes

To take in a series of paintings at a gallery is to dwell with them in an architectural site: their colors vibrate in the light and shadow of the hall as people pulse past them, to and from their sheen, wishing to run hands over the sensual surfaces and forms that change with distance and perspective. All of this is gone from the two-dimensional space of the flat screen, illuminated and equipped as it may be with a focusing technology. It’s gone, too, from the printed page, although in the case of Mary Heebner’s Muse series, the paintings are paired in a stunning book with the late-life poems of Pablo Neruda, her watery hues transposed with his dreamy reveries, each medium lending the other a remarkable resonance.

That book is Pablo Neruda: Intimacies: Poems of Love (Harper Collins, translations by Alastair Reid), the hinge of the ongoing exhibition of Mary Heebner’s work, Intimacies/Intimismos at Edward Cella Art + Architecture in Los Angeles’ Miracle Mile arts district (facing the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), with an opening reception on March 6, 2010 sponsored by the Consulado General de Chile en Los Angeles and ProChile, honoring the 200th anniversary of Chile’s independence. Part and parcel of the educational and cultural programs Edward Cella so adroitly adds to each exhibition are an illustrated lecture by Dr. Judy L. Larson, “How Women Have Shaped and Influenced Modern Art in America” on March 20th and a bilingual poetry reading by Neruda scholar Enrico Mario Santi and Mary Heebner from the Intimacies book on April 3rd. The exhibition continues through April 17, 2010.

Selections from the sixteen

paintings of Mary Heebner’s Muse series (each later named after one of Neruda’s poems) and from eleven

recent

larger works in her Muse: Elements

series beguile the spectator with layers of luminosity at once earthy and

ethereal, tender and bold, their nude figures usually detectable in gender and

number but sometimes present simply as bodies fluidly in motion or even in

embrace, perhaps with a shadow or a memory or a desire. Standing before a work on the wall, the onlooker

becomes an in-looker, pulled into fields of texture and tone that emerge and

recede, fuse and dissolve or crack into fissures and darkness only to burst

into billowy light. Interiors riddled

with wear, ripe with love and longing, speak of a depth of living as clearly

and gloriously as words on a page. Paper

pounced or pursed, rippled with a river that curves its way to coppery silt, winding

through time and remembrance, is the painter’s call to the poet, the cavernous

intimacy of her nudes as rhythmic as the spill of his words, his lines as full

and free as the pigment of her figures.

“October Fullness” / “Pleno Octubre”

38" x 25" approx., powdered pigment, copper,

graphite,

binder, acrylic on handmade Sekishu paper

Writing, be it with brush or pen, is bound up in place because our feelings are steeped in where we have been; thus the mind is a mass of associations “more poetic even than actual,” notes the marvelous Eudora Welty, who painted all the while she wrote. So she knew that the great strides in art brought us not the likeness-to-life of a place but its mystery, and “it was the method, not the subject, that told this.” That method, the musing of an artist, sees in a place an identity that outlasts our own. And so Neruda tells us,

I breathed the air of so many places

without keeping a sample of any.

In the end everyone is aware of this:

nobody keeps any of what he has,

and life is only a borrowing of bones…

And yet in that tumble of water and the day,

of sun, salt, sea-light and wave,

and in that unwinding of the foam

my heart began to move,

growing in that essential spasm,

and dying away as it seeped into the sand.

Neruda died — was it before, or after, that “October Fullness” — on September 23rd, twelve days after his beloved friend, Salvador Allende, was assassinated on September 11, 1973. “October,” a word so multivalent with imagery of political storm or nature’s harvest is here a burst of life, a cry, a sigh, “the sum of all action.” A collective and personal history woven into this paean to commitment resides differently in a painting with the turn of a body from a shadow, the trace of a cupped hand, and in a later iteration, “Thunderhead,” the pigment sifting through that hand, and a pregnant cloud looming with promise.

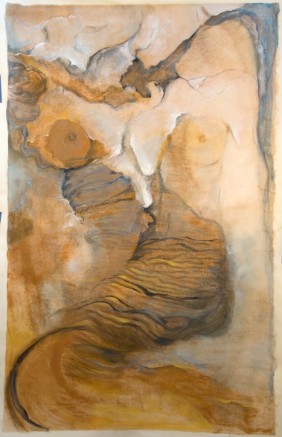

“Canyon Muse” 62” x 42”, mixed media on paper

Deep Living: Place and Cipher

In Heebner’s paintings, a body is

a landscape of feeling, a nexus of recognition and memory, a topography of others

in and as oneself. It may house lavas of

emotion or lacunae of irretrievable loss, terrains oozing with ores or streams

turning to slough — or even ancient ruins rising for discernment. Heebner’s encounters with real and concrete places,

old and abandoned, deliver her to homes that enshrine the spirit. There conduits

of pain, fear, outrage, and doubt take on the care and caress of lovers.

“Discovery,” Welty tells us, “not being a matter of writing our name on a wall,

but of seeing what that wall is, and what is over it, is a matter of

vision.” Mary Heebner’s traveling, turning

lens — of ceaseless mediation that dilates the world and for a moment rests

still — is her ground conductor of belief and conviction, her own poetry of

pigment in water, paint on paper.

Moving in and out of the depths of her subject, the interior strata of the soul and its surface tensions, she unearths her own histories in those of others. Neruda writes in “Loves: the City” of student love in the heart of Chile’s spring, “igniting with October, with cherry trees on fire in the poor streets”:

I think now that my poetry began

not in solitude but in a body,

another’s body, in a skin of moonlight,

in the abundant kisses of the earth.

That was youth. In “So Much Happens in a Day,” looking back in anticipation of a reunion, he asks,

Who would have said that the earth

with its ancient skin would change so much?

It has more volcanoes than yesterday,

The sky has brand-new clouds,

the rivers are flowing differently…

And so, when I greet you

and kiss your mouth,

our kisses are other kisses,

our mouths are other mouths.

binder, acrylic on handmade Sekishu paper

Neruda’s words are so full with time, and his love of people so wide, that it’s not being simply literal to fathom “other mouths” through Heebner’s eyes as she transposes his images with her own voluptuous waterworks that harbor memories of birthing, mothering, providing for a child, traversing the world with a new companion. The layers of musing are to be “discovered,” in Welty’s sense, by participating viewers who gaze committedly upon an ancient gorge carved by movements of deep earth or mighty rivers, visible in a painting as sub-strata of pigment or passages of pentimento display life’s turns and transformations. Surface formations of copper luster, the hand-made ripple where water meets sand or the smooth silt where it recedes, are alive with metallic sheen rubbed into the paper with working hands, fingerprints that retrace, even with a wispy graphite line, the route of travels far and wide, inside.

Neruda’s own work and travels took him to both sides of the Pacific and to Spain where he fought at the front. In 1939 in the abbey of Montserrat, Galeano tells us, the militias published his verses by printing them on paper made from rags of uniforms, enemy flags, and bandages. In “Sweetness, Always,” a treatise on the poetics of everyday life, Neruda writes, “Someone soiled his hands to cook up so much sweetness.” Both the fighting and the writing are other forms of love that reside deep within the artist through waves of time. In “I Ask for Silence” he reflects, contemplating his impending death,

…but the mothering earth is dark,

and, deep inside me, I am dark.

I am a well in the water of which

the night leaves stars behind

and goes on alone across the fields.

Yet even at this time, “it is early. The light is a swarm of bees.”

“Muse of Deep Earth”

62 “ x 42”, mixed media on paper

That regenerative joy abounds in Mary Heebner’s oeuvre. And it’s not as if the figures in Muse: Elements are mere ciphers of the artist’s past to which only she holds the key; these bodies are scintillatingly sexual, luscious in volume, curve and rhythm as shapes fan out, meld and fuse, as delicate lines and feathered edges breathe the pleasures of the air. Paper printed with a pattern or creased from pressing, or in the Muse series, puckered from shrinking, becomes a new bed for powdered pigment doused and spread like sand in tides, paint brushed like the wind over pools. The Sekishu paper of kozo pulp from the mulberry plant has its own history of creation, enjoyed in “just watching how the dragon clouds of fiber merge and mingle in water as they overlap and weave together to form a tight sheet,” the artist recounts. “My ideas grow out of the interaction with what happens,” she tells us, a small reminder that process, in creating as in living, is the key. Her figures derive from neither photos nor models: “I know what the body looks like; I’ve lived in this skin for over fifty years, so I use that as a reference point,” she smiles.

Language

Mary Heebner’s “Westlands Muse” is another iteration of her earlier painting paired with Pablo Neruda’s “In Praise of Ironing.” His words proffer a fascinating thesis of poetics and politics, of life’s work to be done, with luminous sexual connotations. Paradoxically, his reference to “smoothing out” as the task of poetry complements her “pursing up” paper as a process in painting, the former a quest for a return to innocence, the latter a path toward a celebration of experience. “Poetry is pure white,” begins Neruda. But let’s set his page beside her paper as he continues:

It emerges from water covered with drops,

is wrinkled, all in a heap.

It has to be spread out, the skin of this planet,

has to be ironed out, the whiteness from the sea;

and the hands keep moving, moving,

and the holy surfaces are smoothed out,

and that is how things get done.

“Wetlands Muse”

62” x 42”, mixed media on paper

Lay his work, craft, political struggle, and social influence beside her journeys to time-honored shrines, long-since devastated or worn down, resurrected in cracks and crevices she accentuates — a mani wall’s conspicuous “fossils” of color that trickle down her paper like minerals weeping from sandstone in the brilliance of Canyon Muse, or iridescent copper powder that sizzles over an organically crimped surface like the sun wrinkling skin. Neruda’s “canvas, linen, and cotton come back/ from the skirmishings of the laundries,” while Heebner’s shards of history get pieced together anew. Forces trade places in her work: a seed she carried in her womb while painting in Canyon de Chelly, White House Ruin, grew up to become “Sienna,” her daughter, who in turn became the mother’s guide from Kathmandu to the walled kingdom of Lo Monthang in the Himalaya — from another canyon to a plateau between mountain peaks.

It’s no wonder that Heebner paired her poems with Neruda’s paintings. If her influences are the “anonymous ancients" who offer a cultural vocabulary through the act of “musing,” she reminds us that language consists not merely of words — that if words can “paint,” paint can “talk,” and those ancient angels have much to say before “innocence (is) recovered from the foam.”

Whether her travels and desires have taken her to Neruda’s home in Isla Negra or to an exclusive excursion of the caves of Lascaux, to Canyon De Chelly in the American Southwest or Kali Gandaki Gorge in Nepal, the artist reflects,

“… an intense experience in a natural site imbues a place with a sacredness that demands something of me… to touch the nerve of being alive and connected to land and people across time… (despite) impermanence, the nets of translation and the holes through which meaning slips.”

Mary Heebner has been celebrated for her abstract paintings and her handmade art books, with her works held in the J.P. Getty Research Center, the New York Public Library, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Harvard University, among others. Her paintings have been published in two books of Pablo Neruda’s poetry — On the Blue Shore of Silence, Poems of the Sea by Pablo Neruda and Intimacies/Intimismos: Poems of Love. In 2006 Mary Heebner’s work was showcased as a solo exhibition at UCLA’s Fowler Museum. The Intimacies/Intimismos exhibition debuted at the Queen Sophia Spanish Institute in New York City in 2009 and is making its West Coast debut at Edward Cella Art + Architecture.

Intimacies/Intimismos Mary Heebner

Edward Cella Art + Architecture

March 4 – April 17, 2010

Photos courtesy of Edward Cella Art + Architecture

All quotations of Pablo Neruda are excerpts from his complete essay or poems; poems are the translations of Alastair Reid in Pablo Neruda: Intimacies: Poems of Love (Harper Collins, 2008).