1-2-10

Letters to Father Jacob : A Love Story for the Faint of Heart

By Diane Sippl

How do we treat people who are less well off than we are; who is to decide who is fit to live and who isn’t? When life turns out differently from what we were hoping for, then it’s still — yes — A LIFE.

Writer-director Klaus Härö regarding his third feature film, A New Man

The 11th Scandinavian Film Festival Los Angeles will hold its gala with award-winning guest Klaus Härö on-hand on January 9th at the Writers Guild Theater in Beverly Hills (135 S. Doheny) to introduce his fourth feature film, also his third to be submitted to the Academy Awards in the Best Foreign-Language Film category. Letters to Father Jacob arrives from Finland, Härö’s home, even though his previous films were made in conjunction with Sweden. The SFFLA will showcase the Oscar submissions from four other Scandinavian countries as well — Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden — as it offers four days and nights on two consecutive weekends of highlights of recent Nordic cinema. As always, the cinematic smörgåsbord continues in the lobby where industry professionals, émigrés, and film-lovers mingle and down a glass of brew with sauna sausage or soup and salad as they digest the delights of the screen.

By this point in his illustrious

career, Klaus Härö has earned the label “auteur” in the best sense of the

word. It’s not that he never

collaborates: his stories often come from others, whether prolific authors such as Kjell Sundstedt for Elina

and The New Man or budding

screenwriters such as Jaana Makkonen for Letters

to Father Jacob. Härö also works

with award-winning cinematographers, here, for example, Tuomo Hutri. What distinguishes a Klaus Härö film is his

ethics and the graciousness with which they take center stage in his works. His

insignia is the way he fills his wide, wide frames with something as elusive as

human frailty that comes over us unawares, for in that frailty there is beauty to be

found, a seed of strength for each of us.

Yet on a given day, most of us feel strong enough. Leila does, even though she’s been sentenced to life in prison. At a certain point, she was big for her age, able to do men’s work, ready to fend for herself. And when she ended up behind bars with a life sentence for murder, she didn’t want any contact from the outside. Now after twelve years the warden is forcing her out on the basis of a pardon and placing her in the vicarage of a blind priest to be his personal assistant. Alone out in the countryside, Father Jacob fares quite well, Leila discovers — in fact, he gets around too cleverly, and he soon annoys Leila.

A profound generosity of spirit pervades the creaky old rectory and its garden as if it rises from the reeds in the marsh or the breeze in the birches, but it is most apparent in the piles of letters packed under the pastor’s bed, either answered or waiting for his attention. It most certainly is not a matter of the wad of money he hears Leila unfold from the envelope used to return it, the recipient having sent back the extra to the priest after she used a pittance of his gift. Yes, Father Jacob had given the woman in the letter his life savings. But it’s really another kind of gift he offers — the charity of an open heart, the compassion to understand, and an unselfconscious modeling of the humility to forgive. To Leila, he’s a lunatic, and she would sooner tie a noose around her neck than put up with his relentless and seemingly pointless insistence on the encouraging word, the note of support; yet these very words are a lifeline for her, if only she can grasp it.

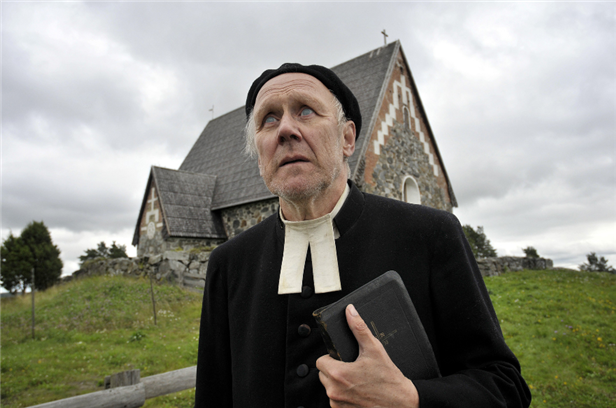

Meanwhile Father Jacob (a

masterful Heikki Nousiainen) succumbs to a crisis of conscience: the letters stop coming one day, and he no longer has a way to be of use. What does one make of life without being able

to serve a mission? Of course, Leila has

tossed a number of the letters into the well out of spite, and then again, the

mailman has stopped coming out of fear; she is, after all, a foreboding

presence.

Letters to Father Jacob may seem at once too easy even for children and too complex for wise men and gurus. The more natural it appears, the more enigmatic it becomes. It is both believable and unbelievable in the same moment that Leila (the phenomenal Kaarina Hazard) loosens the fret on her forehead. What her eyes show in this transition, we see but cannot know. As for Father Jacob’s eyes, their sky blue pierces us with their immobile vastness (and the eerie feeling that we are looking at the filmmaker in his old age). The occasional extreme angles of the camera and the stark sunlight with dark shadow let us know that we are gazing upon two iron-willed individuals, but even iron rusts in the dew, and the ambience is literally dripping with transformation.

In a scant 75 minutes, a Haydn string quartet, a Beethoven minuet, a Chopin nocturne, and an Offenbach barcarolle are softly heard as we travel through the film with the cadence of the human heart, often noting only through a long shot the significant action at the end of several chambers. Klaus Härö condenses his story to its most potent form, distilling its beauty at each turn. In essence, then, his Letters to Father Jacob is a vessel of faith and hope, an elixir of love.

Heikki Nousiainen as Father Jacob

Writer-Director Klaus Härö

Letters to Father Jacob

Director: Klaus Härö; Producers: Risto Salomaa and Lasse Saarinen; Screenplay: Klaus Härö; Cinematographer: Tuomo Hutri; Editor: Samu Heikkilä; Production Designer: Kaisa Mäkinen; Music: Dani Strömbäck; Costume Designer: Sari Suominen; Sound Designer: Kirka Sainio; Original Script: Jaana Makkonen.

Cast: Kaarina Hazard, Heikki Nousiainen, Jukka Keinonen, Esko Roine.

Color, 35mm, 74 minutes. In Finnish with English subtitles.