7-8-16

The Gift of Godard: Contempt Serves Well

By Diane Sippl

For Godard, more than for any other figure in the cinema, film and reality are one and the same thing.

Colin MacCabe, Godard: a Portrait of the Artist at Seventy, 2003

Every day to earn my bread, I stand in the line where dreams are sold, and hope that I take up my place among the sellers.

Bertolt Brecht, “Hollywood”

The eye… is the key piece in the film actor’s game. One only looks

what one feels, and what one does not wish to reveal as one’s secret.

Jean-Luc Godard

A young independent filmmaker told me that viewing Contempt was like watching Haley’s Comet: he could look at it infinitely and see something new each time. Well on July 14th, Bastille Day, the American Cinematheque’s Aero Theatre in Santa Monica will launch a 4-day celebration of “French Favorites” ranging from Jacques Tati to Henri-Georges Clouzot to Jean-Luc Godard to Jacques Demy. In Contempt, showing on July 16th, SoCal viewers can ponder the cosmos in the eyes of Godard and see his sixth feature film as both the most scintillating capsule of his oeuvre and the most tragic embodiment of his life.

Contempt solidly delivers Godard’s vision and his voice, but perhaps like no other of his works, it surprises us with his valor. It’s amazing to see him work out that valor, not just with the bravura of a developing filmmaker taking bold new strides, but with the courage of his humility, as an artist and as a man.

In 2012, Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt turned 50, and the Village Voice pointed out that in New York it seemed Film Forum had by then “turned revival and restoration of the picture into a cottage industry,” holding it up before us anew in 1997, 2008, and then again in 2013. Contempt was called a “romantic tragedy,” but as such it’s a strange brew and deliberately so, marking a double loss — of classical Hollywood cinema and of marital love — folded into one and vanishing in the world of ancient gods who spell havoc for the hubris of man. The film’s strangeness is also twofold, stemming both from Godard’s view — of an industry hollowed out by the marketplace, eaten away by its own capital and new media competitors — and from his way of expressing it — via the “alienation effects” of Brecht’s epic theatre that the young activist-artist Godard deployed as strategies for cinema. He used language (image, sound, words, and their combination) differently from the ways his filmmaking precursors had.

Godard, like Brecht, has always brought us theory, wrung out of his own hard, risk-taking work. And why was that so important? Because it showed us (as Brecht did with theatre) that cinema, if not the world, could be re-made. But Contempt was also vital because in making it, Jean-Luc Godard showed us that his thinking could set us feeling: for example, that there was a way to ogle the famous beauty, Brigitte Bardot, that would let us see how two tragedies — that of filmmaking in the hands of Hollywood and that of women as the objects of men — could be one. For all of Godard’s wealth of text in this film (visual and starkly verbal, printed and spoken, dramatic and mythic, quoted and cited), the unforgettable

sadness of Contempt comes over us as purely emotional. Intellectually stimulating and politically shrewd as the film is, Godard is at his best in Contempt because he is most himself: as naive as he is brave, as insecure as he is bold, as vulnerable as he is candid.

Godard’s cinematographer, Raoul

Coutard, has said that Contempt was

the most expensive postcard a man ever sent to his wife. Godard made the film he

needed to make to see himself — as a writer (embodied in Michel Piccoli), as a

director (in the guise of Fritz Lang), and as a husband to Anna Karina (played

by Brigitte Bardot). If cinema was his

mistress, he feared he would also become Hollywood’s

whore, and he needed to come to terms with both of these excesses of filmmaking

in his early forays as the Ulysses of the nouvelle

vague. Contempt was the most

conventional, the most commercial, and the most expensive film Godard had made,

and yet it was his most piercing critique of the Hollywood he had once loved. According to him, it was also the end of his

marriage.

In Contempt, Rome is the tentative residence of a Parisian couple, one-time typist Camille (Brigitte Bardot) and her sophisticated crime novelist, would-be-playwright husband, Paul (Michel Piccoli), who has been asked to sex-up the script for a movie re-make of Homer’s Odyssey, an Italian-American co-production at Rome’s Cinecittà. The film, written and directed by the elderly Fritz Lang, who plays himself, is screened as a rough cut that upsets its American producer, Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance), except for a nude scene of what his secretary-translator Francesca (Giorgia Moll) refers to as a “mermaid” swimming in the Mediterranean who fills his face with the guilty grin of an adolescent boy. Prokosch is a snake in the grass. Why does he think Paul will accept his offer to doctor the screenplay? “You have a beautiful wife,” he tells Paul in Godard’s typically ambiguous language that effectively ties the two major losses of Contempt — marital love and love of cinema — together. While Prokosch throws fits by hurling film cans as if he’s a discus thrower, Lang stands by as a one-man Greek chorus and also a reality check on the studio system’s mode of production, whether in Hollywood or Paris or Rome, where Cinecittà is visibly lying in ruins as Contempt opens.

Prokosch, nonetheless, struts himself as a god who mandates “yes-or-no” answers, for example when he invites the young couple to his home for a drink and there is room for only one — Camille — in his red Alpha Romeo “chariot.” Paul insists that he will catch a taxi there and arrives half an hour later, much to the simmering rage of Camille. Soon thereafter she is subjected to a glimpse of her husband’s butt-pat caress of Francesca after he excused himself to find the bathroom. “Is this how you wash your hands?” retorts Camille, who has by now reached a point of no return in her marriage.

It didn’t happen over night; we entered the film “in the middle of it” in more ways than one, except that it’s a rather lopsided love-making scene for us to intrude upon. Camille and Paul are both in bed, but she is naked and he is dressed; as elsewhere, she is begging his attention (“Do you love all of me?” she asks, after inquiring about each of her body parts for adulation), and he is one foot out the door (“Yes, all of you. Totally, tenderly, tragically,” he replies.)

The scene runs parallel to Godard’s own mandates from his American co-producer of Contempt, Joe Levine, to wring more sex out of Bardot for his money (she was then, in 1963, at the height of her celebrity).

Godard complied, with this extended opening “nude” scene in bed that is yet so emotionally disorienting, with Coutard’s prolonged shots under alternating filtered light — first red, then white, then blue — that we can’t help but detach and reflect as we gaze upon the couple. Our erotic voyeurism is disrupted by the core sexual politics of the film (or at least, as Godard has pointed out, the colors of the French and American flags).

Both personal and political as

these marital relations are, they usher us right into Paul’s professional

predicament: he would like to be a man of action, a clear and forthright outlaw

or cowboy cut of the swath of American movie heroes from the films of Lang or

Hawks or Hitchcock, as swaggering as Prokosch (a 73-year-old Jack Palance did one-handed

push-ups, front-center-stage, in receiving his first Oscar in 1992), but Paul feels

himself a postwar, post-Hollywood, European intellectual riddled with

self-doubt. This mix makes Godard the

artist, if not Paul the character, a lasting fascination. Can he surrender his dignity to doctor Lang’s

script (or his own), succumb to Prokosch’s (or Levine’s) god-like braggadocio? Has he already sacrificed his wife at his

producer’s altar? Selling out to

Prokosch, Paul pockets his check like a whore-turned-pimp: his wife will be the

next trophy. Just as we entered the film

in the middle of a questionable love scene, Contempt

began in the middle of the production, too, and it has already gone bad.

We can peel back the layers to

the source: Homer’s Odyssey; Rome’s Ulysses; Alberto Moravia’s novel Il Disprezzo, which Godard adapted for

the film Contempt; Lang’s script for

the film-in-progress within the film; Paul’s doctored re-write for the film

that will never be produced; and finally Godard’s Le

Mépris (Contempt), a polyglot of

languages translated with deft nuance that deliberately defies a monolithic

reading. The most precise is Godard’s

own voice-over announcing the credits at the opening, owning the film

indisputably despite what will come to pass as a heart-wrenching critique of

ego in both spheres of love — of women and of the cinema — undeniably Godard’s

own in terms of his then wife, Ana Karina, and the making of Contempt itself. It may be that Georges Delerue’s music

dictates the tone from the film’s first moments, but the score’s subsequent

crescendos never wring false or superfluous.

Jean-Luc Godard seals the signature as the film closes, playing the role

of the assistant director himself, one of the few characters on the set who is

not an archetype.

Coutard’s long, slow tracking shot with Godard’s voice-over for the opening credits; the extended choreography of a husband-wife, on-again-off-again quarrel in the couple’s semi-furnished apartment; the costuming of Paul toga-toweled or half-dressed in Dean Martin “cool” throughout that twenty-five-minute domestic pas de deux; the other doubles there (the lifeless statue of Bardot as a fixture in the living room, the black wig she dons evoking Ana Karina, Bardot swimming finally as the mermaid-on-the-run in counterpoint to the earlier mermaid erotica in the rough footage projected) — all call our attention to the artifice of the cinema and invite us to reflect on its mechanisms and our complicity in accepting them, to move us from passive to active viewers. Godard confronts us with the level of pain, loss, and sorrow that he himself experienced in making the film before our eyes, letting us understand why the emotion in Contempt rings so true. In traversing that distance between what has been lived and what has been created (though they may seem like a hair apart), we make the cinema — and not just this one film — our own.

In Contempt, even with all its recitations, poster references, and

kitsch iconography, we are hardly aware of performing this feat, as invested as

are we in the sadness of its world. Turning

Bardot’s body into an alienation-effect that situates us as disoriented voyeurs

was a trick Godard pulled on his producers before it ever registered on us. Replacing Piccoli’s body with Godard’s at the

close of the film lets us see Paul’s anguish as the filmmaker’s. Paul has waged money and fame against

integrity, a dance as dangerous as bartering the love of his wife, or his life —

the cinema. Godard waged the bet and

won, at least with cinema. And if, as he

said, “Style is just the outside of content,” then the risk of Contempt was its core. Ironies abound: in the aftermath, Michel Piccoli

became a “star” and Contempt “failed”

at the box office, only for this coyly theoretical work to be restored over and

over again, to this day, as Godard’s most accessible film as well as his most

theatrical accomplishment. Yet the

reason: in Contempt, Godard dared to

bear his soul.

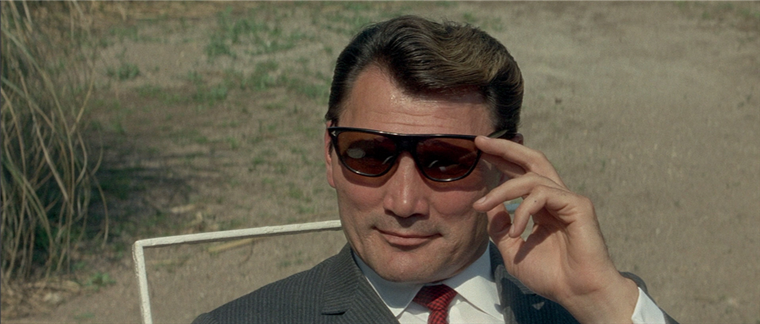

If Paul became “cool” as Piccoli but never as Camille’s insouciant husband, it was owing to Godard’s own personal style and taste — perhaps less the fedora, tie, and signature dark glasses he wore, but even more, the costumes of his actresses with their knee-length, high-necked chemises and pleated skirts, the timeless ballerina walk of Bardot, the classical dimensions and epic poetry of Lang as he worked in Hollywood, his pin-striped suit and monocle a throwback to the glory days — that allowed Contempt to join the ranks of Homer as a classic of world arts. After all, it is classics that are cool.

Today Contempt is arguably the most astutely observed and painfully eloquent testament to the challenges young Parisian intellectuals faced in forging what came to be called French New Wave cinema. As for the sexual politics, Godard was on Camille’s side in Contempt; from the outset she was no femme fatale. The mutual complicities at hand are not between a wife and a husband, as we might come to the film expecting, but between Paul’s infatuation with the cinema and the contempt of the studio system for its workers and its audiences, and even, as in Paul’s case, contempt of self.

Godard enchants us with the shimmering seascape of desire that seduced Odysseus in his caprices as we follow Paul’s journey to sadness. The film’s beauty is irresistible, its pain palpable. It is often remarked that Contempt is Jean Luc Godard’s least characteristic film — his most conventional — yet his most masterful. Just the same, his dense, esoteric, distancing language is everywhere. Yet with all his artifice, Godard has brought us truth. In Contempt, the most poignant paradox is one Jean Luc Godard has always known: beauty brings melancholy in anticipation of its loss. The purity of beauty’s truth is fleeting. As in cinema, its moment is ephemeral, even if, as with Haley’s Comet, we could gaze upon it forever.

Contempt (Le Mépris)

Director: Jean-Luc Godard; Producers: Carlo Ponti, Joseph E. Levine; Screenplay: Jean-Luc Godard, after Alberto Moravia’s novel, Il disprezzo (A Ghost at Noon); Cinematographer: Raoul Coutard; Editor: Agnès Guillemot; Music: Georges Delerue; Sound: William R. Sivel; Costumes: Tanine Autré.

Cast: Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, Jack Palance, Fritz Lang, Giorgia Moll, Jean-Luc Godard, Linda Veras.

Color, 35mm, Franscope, 110 min. In French, English, German, and Italian with English subtitles.