10-24-10

The Paradoxical Carlos: Olivier Assayas Around the Globe

By Diane Sippl

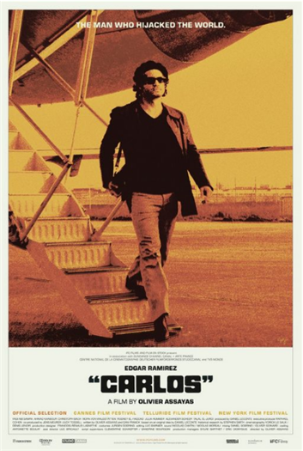

The sprawling lawn of the Résidence de France in Beverly Hills evoked the green gardens of Summer Hours, Olivier Assayas’ last film (2008). Like the genteel characters in that crisply lyrical update of Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard in the Parisian countryside, Assayas struck a fine profile. His salt-and-pepper hair and silky, dove-gray cardigan framed the black intensity of his eyes as they darted after the words he used to express himself. His finely chiseled face reflected the intellectual acuity of his remarks; they arrived with exacting precision. But soon enough clouds, dark and billowy white, raced across the October sky as we discussed the elusive yet seemingly ubiquitous “Carlos,” whose iconic image on the tarmac of the Algiers airport was captured through a long lens in 1975 as he negotiated the fate of the OPEC oil ministers, a fate that would seal his own.

For a keenly etched portrait of “Carlos the Jackal” (as the press referred to him then), Olivier Assayas left the idyllic French landscape he knows so well to create an epic of late-20th-century terrorism, chronicling the actions of Ilich Ramírez Sánchez’ across two-and-a half decades and ten countries on three continents, in eight languages with possibly as many dialects spoken by well over a hundred actors. A spearhead of pro-Palestinian activism, a player with the Japanese Red Army, and a commander of German members of the Revolutionary Cells, Carlos (Ramírez’ new pseudonym in 1970) soon donned the look of “Che” in the name of radical leftist politics even if only to become an obsessive mercenary for the highest bidder. Paid and/or protected by the powerful secret services of a variety of nations across the Middle East, Europe, and Africa, he enacted both covert and overt operations, such as hostage-taking in the French Embassy in The Hague and in the OPEC headquarters in Vienna. As vain as he was violent, Carlos, whether he knew it or not, also had to contend with his own lust — after fame, money, and women — as he played his hand on the world stage.

Based on meticulous historical and journalistic research, Carlos is nonetheless a dramatization of a man who could be as charismatic as he was dangerous all the while he dug his own grave through the Years of Lead. Yet in this docudrama, if one could refer to such a colossal account as such — in this fiction, let’s say — are the facts of terrorism, of geopolitical destabilization, that made the world as precarious as we know it today. If the film might resonate more with Dostoevsky’s “demons” or Conrad’s “secret agent” over a century ago than with Fassbinder’s “third generation” or Bellocchio’s “China” or Godard’s leftist theories of the 1970s and 1980s, this is because despite the punk music and period detail, we are in the grip of black-and-white, life-and-death moves even as we see them in living color and CinemaScope dimension. No romantic or sensationalizing biopic, Carlos is a steely study of deadly politics before our very eyes. The “in-broad-daylight” aesthetic of both the narrative and the images, on top of the scale of the production, makes Carlos an original feat, potentially as globally impacting as the man himself.

Assayas has directed sixteen films in twenty-four years — that is, if we count the 330-minute Carlos, his latest, as one film and not three — and has written them as well, along with numerous publications on international cinema (focusing on luminaries as diverse as Ingmar Bergman, Kenneth Anger, and Hou Hsiao-Hsien). Having studied painting in his youth, particularly Impressionism, and having written for the esteemed Cahiers du cinema, he then used Paris as a springboard for making seemingly two kinds of films, one strikingly Francophile, steeped in the arts and literature of his country, and the other decisively international, consciously or unwittingly influenced by his mixed ancestry (a Hungarian-Austrian mother and a Jewish Italian father with roots in Greece who also lived in Argentina, screenwriter Jacques Rémy, both parents having emigrated to France, where Assayas was born and came of age in the midst of his father’s work in cinema and television).

To get a new handle on the shifts of global power from the end of the 1960s to the middle of the 1990s — both in the headlines (telescopic) and behind the scenes (microscopic) — I asked to know more about Ilich Ramírez Sánchez. Who was this character, “Carlos”? What drove his politics, his psychology? How strong were his convictions? Did his relations with women reveal his personal feelings? I also asked for elaboration on the intricacies of Olivier Assayas’ research and writing, the orchestration of Carlos’ many escapades, and Assayas’ orientation to the conventions of film genres relevant (or in his eyes, irrelevant) to the substance of his film.

Diane Sippl Can you tell me about your approach to fact and fiction in creating Carlos? I recall that as I viewed your film, the news footage played an important but somewhat unusual role. Every time I saw it, I wondered whether it was real old footage, or reconstructed, or perhaps even newly shot.

Olivier Assayas The original screenplay called for much more news footage. There was much more historical context, and I even started editing the first part of the film with all those capsules of context of the times, specifically dealing with the Israeli-Egyptian peace process and the countries who were opposing it. And then after awhile I realized it did not work. It broke the narrative. So at that point I just discarded most of the stuff and I used the news footage only at very specific moments when it integrated in a seamless way with the narrative, when there were basically scenes that I could have reconstructed in one way or another. This footage is not like something that gets you out of the narrative to give some kind of bigger picture; it’s more like actual facts connected to whatever we’ve been building up in the story. So that’s one part of it.

Another part of it was that I wanted to have — especially concerning the most brutal operations of Carlos — a way of bringing back to the audience the notion that this had actually happened. That yes, those guys that we have been following — we’re not exactly close to them, we don’t exactly like them, but still we’ve been involved in the logistics of whatever they’ve been doing — they were actually planting bombs and those bombs were killing or mutilating actual, real-life people. You know with every single operation, I just wanted to show the reality, just to bring back the fact that this was really how it actually happened, and it was not just fiction.

Also, I used footage of the victims. With every operation, I show a real-life individual who has been hit by the bomb, the operation, and this is real footage.

DS So all the news footage already existed, and you had access to it.

OA Yes. Absolutely. The only moment when I “played” with the documentary footage was once, or twice actually, when I used the previous shot from the film, which I kind of faded to black-and-white to move into the actual news footage. So there’s a kind of fade into those scenes to make the transition seamless.

And the other thing I’ve done — which is the only time I didn’t exactly cheat but “played” with the news footage — is the interview of Chancellor Kreisky in Vienna, because I had this really great footage of the press conference; it did exist. I needed the press conference of Kreisky in the film. And when we researched it we found really excellent footage of it, of the journalists, and so on, and it was edited — you had the whole scene and then you had this shot of Kreisky. And at that point I decided I would use the footage except I would insert our actor.

DS So the background is real, and the face and body are injected into it.

OA Exactly. The other shots, the specific shots involving Kreisky, are our actor.

DS So that’s the only time you did that?

OA Yes, absolutely.

DS So then we don’t have to worry that you’re fabricating some footage — which would be okay, a choice, but we don’t have to worry about that choice.

OA No, not at all.

DS Very interesting, and it goes along with all of your very strict authenticity throughout.

OA Yes, because I also had a sense that injecting, at specific moments, historical footage that connected intimately with the story we were telling was a way of reminding viewers of the precision of our research in a certain way.

DS I admired your principle of shooting and casting in the real locations and insisting that the actors use the exact languages of the locales. I also marveled your ambition to do this.

OA Yes, for me it was essential, because most of the Western films dealing with the Middle East, as you know as well as I do, are shot in Morocco, because that’s the place where you find the logistics, where it’s more Western-culture-friendly. And often, because it’s easier, these films are also cast in Morocco, meaning that most of those movies use Moroccan-French or French-Moroccan actors, which gives the illusion that the Middle East is populated by Maghrebians (northwest Africans of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia), which is of course absolutely wrong.

Syria, for instance, is one of the most mixed cultures. In Syria you have blonds with blue eyes. You have every kind of person in Syria. And again, the ethnicity in Syria is extremely different from the ethnicity in Iraq, or even Lebanon to some extent. And then, it has nothing to do with Iranians, or Persians.

So I think if you make a movie dealing with the geopolitics of those times, specifically the geopolitics of the Middle East, you have to get it right. You have to get the cultures right. You have to get the accents in Arab right. It’s something that, for some reason, Western movies just don’t do, but for me it was vital, because the situation in the Middle East is so complex that if you don’t give the basics, people just keep seeing it as this completely inextricable mixture of half-unreadable signs. Here we tried to be as clear as we could.

DS And still, there were, when you were writing it, some mysterious areas in the biography of Carlos. So I’m wondering how the fiction plays into your film. For example, I didn’t find it a particularly psychological film. So in the end I was asking myself, was he ever really an activist committed to causes, and how would we know? How much did you know about him in his youth or beginnings?

OA Well when we see Carlos in the first scenes of the film he is still somehow the young Carlos, so he is defined by whatever has defined his youth, including the mysteries of that period, and stuff that’s very delicate to handle. He is from Venezuela. He was raised by parents who were militant leftists. His brothers were called Vladimir and Lenin — Ilich (his name), Vladimir, and Lenin — so it’s pretty clear. He was taught at Patrice Lumumba School in Moscow. Up to that point, he is a Third World militant. He is not unlike so many kids of his generation, and he has beliefs; he is also a man of action. He wants to go and fight for his cause. He’s not a big thinker. He’s not a big theoretician, or whatever. He’s just a believer. And he has a lot of physical courage and the will to do things. So the one area that has not been clarified and that is, of course, difficult to deal with, is how he moves from being a student in Moscow to holding a machine gun for the Palestinians in Jordan when he’s nineteen years old — meaning, is there any kind of KGB involvement? Is he or is he not a KGB agent?

There is absolutely no proof that he was a KGB agent. When the KGB files were briefly opened — and instantly closed — Carlos’ KGB file said basically, “He’s a student but he’s too unreliable. He’s too wild and we don’t trust him.” And that’s it. It’s a complicated matter, because Wadie Haddad was a KGB agent; that’s established. And it’s pretty hard to imagine that when Carlos traveled freely in Europe, he could do it without any kind of KGB supervision. What I am saying is that that’s one of the blind spots, and we have to accept that it’s a blind spot. And that’s the background, really, to the Carlos we find at the beginning of our film.

After that, we’ve been focusing on specific moments, and those moments are pretty well documented. What was more difficult, and where obviously I had to use slightly different narrative techniques, is the 1980s, because the 1980s presents a really long period of a lot of extraordinarily complex activity for Carlos. So as much as I don’t consider Carlos a biopic, in a sense, there is this kind of biopic moment, where we had to kind of squeeze into a small amount of time extremely important defining moments of what Carlos is and became and how it led him to the next big chapter which is, of course, Carlos in Sudan.

DS What about the women? We get more of them as the film goes on, and I’m wondering how much documentation you could access about any of his emotional involvement at all. Did you try to stick to fact and evidence rather than your own conjecture?

OA Yes. In terms of reference, the woman we see with Carlos in London, at the beginning of the film, wrote a memoir in which she describes her relationship with him at that time and also his relationship with women. The dialogue with her in the London restaurant, and also the “grenade scene,” which I used in a different context with another woman, come from that book.

We have the book of Magdalena Kopp. While we were writing, she published a memoir of her life with Carlos. Well you know it has to be taken with some care, because she paints a very brutal and nasty image of Carlos: basically she says that whatever she did, it was because she was scared of him, and she presents herself as a victim of Carlos, which is, you know — I thinks she’s also concerned now not to be too involved politically with the activities of Carlos. I mean she’s writing her memoir, and she was politically involved, and she was much closer to Carlos than whatever she says, and she did not have to go to Damascus to join him when she got out of jail. So you have to take whatever she says carefully, but still, you have very detailed images of what Carlos was about during those years.

Then you have the call girls, or whatever, who were used by the Stasi to spy on the Carlos group. That’s also fact — I mean there’s more to it. One of the girls became Weinrich’s girlfriend and did office work for the Carlos group after Magdalena had been arrested. Initially she was one of the call girls who were used by the Stasi to spy on them, but then she kind of joined the Carlos group. So that’s also absolutely established. But you know the non-stop relationship of Carlos with hookers, prostitutes, is in every single account, so that’s a constant of Carlos.

And again, he got into trouble in Sudan, exactly as we see in the film, because he visited a Sudanese prostitute and he presented himself as his alias, Mr. Barakat, a Yemeni businessman. The girl was surprised because he did not have a Yemeni accent, and you know it’s a police state, so she went to whichever secret police guy was around and told him she had to deal with this weird guy who pretended he was Yemeni but absolutely had no Yemeni accent. Carlos gradually became an embarrassment for the Sudanese because it’s an Islamic state and you had this guy who was a drunk and was continuously seeing prostitutes. So there’s a lot we know in terms of the relationships of Carlos.

DS It’s much more than I imagined, so I’m glad I asked, because it’s an interesting question for me. There was always through the 70s and 80s a critique of male revolutionaries because of their sexual politics.

OA But Carlos is very specific. The Leftists were Puritans, at least in France. Well, there was a macho element — there was a very brutal macho element. The guys were doing things and the girls were catering — preparing the food, shopping, whatever. So machismo was part of leftist politics; but then, sex — not so much. Carlos is very specific, and I think one of the reasons he became so visible and became the myth that he did is also because he was so extraordinarily different from Leftism as it was known at the time.

DS What about the genre conventions that surround your film? Were you very worried about them? Were you trying not to let Carlos become a gangster film? And what about iconography from other films? Did you look at films from the time period?

OA No. I lived that period. So I did not need the movies. You know, you have a sense of it.

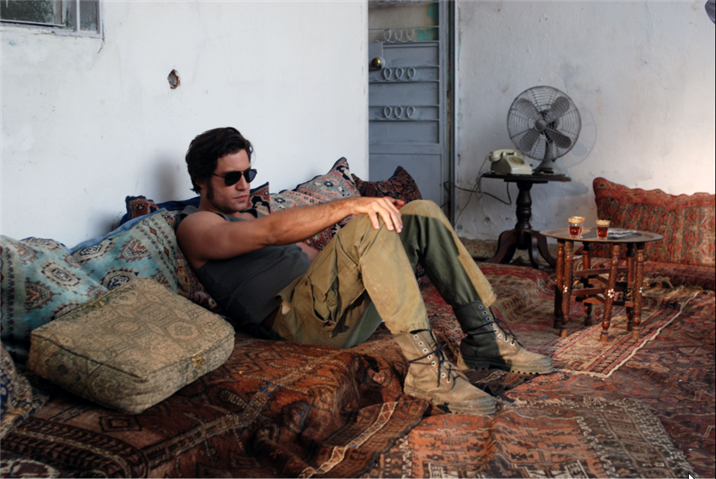

Olivier Assayas (top center) directing Carlos

DS Well it didn’t feel like a gangster film to me, though there were endless suitcases of money or guns being loaded into car trunks. We saw this so many times.

OA Yes, but it’s so much what the everyday life of terrorism is about. I mean, when you read about Carlos, he’s constantly carrying suitcases from here to there and hiding them here, there — it’s non-stop.

DS And then you do it in such a mundane way, it’s interesting.

OA It’s the basics of the job.

DS Yet some critics have referred to your story arc of the guy who starts out with some scruples, maybe, and loses them, and then has his downfall and must face it, as precisely the story arc of the gangster film

OA To me it’s somehow more universal than that in many ways. It’s about youth, middle age, and old age. If you want an arc, that’s the arc — meaning it’s a twenty-year span. But ultimately you have idealism, and then you have the pragmatism of being confronted with reality and having to deal with the complexities and contradictions of reality and trying to adapt to it — specifically what pragmatism is all about. And once you are there, it’s pretty easy to move into areas that have to do with cynicism, when things don’t turn out the way you expected and you end up on completely different ground than where you were heading initially.

And this is the story of Carlos. Once he has been fired from the PFLP by Wadie Haddad, he’s not just fired from the PFLP; he’s fired from the Palestinian cause. At that point, that’s the cause he’s been fighting for — it’s the one thing, the framework, of his politics and political involvement. The PFLP is not just some kind of rogue element in the Palestinian movement; it’s pretty much part of the center of it, much more than is acknowledged. The relationship with the PLO and the PFLP is pretty close, so when you are out of the PFLP, you are out of the Palestinian cause. And from that moment, there is nothing left, really, to give any kind of ideological framework to the convictions of Carlos.

And because he has been killing those cops in Europe, he can’t go back. He’s stuck in the Middle East, and he’s not part of whatever he was involved in before, so he’s left to do whatever he can and work for whoever will hire him. That’s when you move into cynicism. And of course, when the Cold War is over, when he can’t even travel to the Eastern Bloc any more, he becomes irrelevant.

DS Your actor, Édgar Ramírez, embodies an uncanny resemblance to Ilich Ramírez Sánchez. They share a lot: name; home town in San Cristóbal, Venezuela; time spent in Caracas; globe-trotting, politically connected fathers and families; and facility with languages (Édgar Ramírez speaks five languages fluently in the film, plus some Arabic). Did you use any kind of special directing technique distinct from that used in your other films? People have mentioned Method acting, even a resemblance to Brando in Édgar Ramírez — is that all conjecture? Was there any special way of working with him?

OA No — I always give a lot of space to my actors, and somehow they use it, or they don’t use it. In the case of Édgar, he used plenty of it. Édgar just took all the freedom he had and appropriated the character, and we made this film with such a close connection.

DS Can you tell me one last thing?

It’s a big film, and I’ve seen a number of big productions lately about mythic

characters of the period, even fairly international figures such as Che

Guevara, Andreas Baader, and Ulrike Meinhof, who became icons, and also Jacques Mesrine,

the bank robber who suddenly and wildly claimed a political agenda. You’ve said that you saw

as you got into the story of Carlos how big it needed to be in order to be done

well. I’m interested in your global

perspective. I’ve seen your other films,

nearly all of which have to do with global themes and issues. But your multi-tiered platform for

distributing Carlos — was this part

of the vision once you saw how big the film could be?

Was it something you really worked for to negotiate? How important was the means of distribution

in relation to the size of the film?

OA Well it happened kind

of fast when we were putting everything together, but still, it happened layer

after layer. It was when I realized that I

would be able to make this film based on my own terms — which were using no stars

but

an international cast with the specifics of every single country and culture, and shooting in 35mm, wide-screen format, on this kind of huge canvas — that I kind of realized that what I was doing was not exactly a three-part TV movie; I was doing something much more ambitious than that. I was doing something that could have some kind of international echo. And what I was doing was absolutely a movie. I was doing it for the big screen. So I contributed this concept to the group — I tried to convey this notion to my producers so that they structured the film in ways that allowed it to have this kind of life.

DS You mean a theatrical film in three different lengths (roughly two-and-a-half hours and five-and-a-half hours for theaters and a three-part mini-series for TV); and not only that, but shown in theaters and on programmed cable TV and through On-Demand access as well. It’s really three different lengths and three different modes of distribution.

OA Exactly. And I had to think on two different simultaneous levels. One level was the financing of the film, and the interesting part of it was that the financing of it had to be TV. Cinema was the minority financing; it’s an important part of the financing, but still, the bulk of it is TV money, and it could never have been any other way, because there’s no way you get any kind of major money from cinema for a five-and-a-half-hour film. This is uncharted territory, really. So I had to think simultaneously of the movie I was making, which was a five-and-a-half-hour movie to be seen on the big screen, and the financing, which had to be TV. You know, it’s a complete paradox. A complete paradox — but that’s the reality of this film.

Carlos

Director: Olivier Assayas; Producers: Daniel Leconte and Jens Meurer (co-producer); Screenplay: Olivier Assayas, Dan Franck, based on an original idea by Daniel Leconte; Historical Advisor: Stephen Smith; Cinematography: Yorick Le Saux, Denis Lenoir; Sound: Nicolas Cantin; Editing: Luc Barnier, Marion Monnier; Sets: François-Renaud Labarthe; Costumes: Jürgen Doering; Assistant Director: Luc Bricault; Casting: Antoinette Boulat, Anja Dihrberg, Nicole Kamato, Rosa Estévez.

Cast: Édgar Ramírez, Alexander Scheer, Nora von Waldstätten, Christoph Bach, Ahmad Kaabour, Fadi Abi Samra, Rodney El-Haddad, Julia Hummer, Rami Farah, Zeid Hamdan, Talal El-Jurdi, Fadi Abi Samra, Aljoscha Stadelmann.

Color, 35mm CinemaScope, 330 minutes (Part One: 100 min., Part two: 107 min., Part Three: 123 min.).

In English, French, Spanish, Japanese, German, Arabic, Russian, Hungarian dialogue with English subtitles.