12-19-11

By Diane Sippl

I wish stable, still, impalpable places existed; places which would be references, starting points, sources.

Alike the sand flowing through your fingers, space melts.

Such places do not exist. And because they don’t, space becomes a question [ceases to be obvious, to be integrated, to be appropriate]. Space is a doubt: it’s never mine, it’s never given to me, I have to conquer it.

Tecnologia Filosofica, Canzoni del Secondo Piano

I’ve never intended to invent a particular style or a new kind of theatre. The form emerged quite from itself: from the questions I had. In my work I’ve always looked for something I did not yet know….

You have to try all on your own to make visible what you have always known, or at least give a clue or foreshadow it. It’s about finding something that does not need any question.

Pina Bausch, 2007 Kyoto Prize Workshop in Arts and Philosophy

What Songs from the Second Floor should do, as all art should, is to make life and living conditions clearer and more obvious to everyone.

Roy Andersson, Director’s Statement for the film, Songs from the Second Floor

…Beloved be the one who sits down…

The Italian dance company, Tecnologia Filosofica (“Philosophical Technology”), comprised of five dancers, a singer, and a musician, performed Canzoni del Secondo Piano on December 9, 2011 at the Théâtre Raymond Kabbaz of Le Lycée Français de Los Angeles. Along with their words above that headed the program notes, Roy Andersson was also mentioned as inspiring this particular work, which is named after his film, Songs from the Second Floor. The notes continue, “A succession of trios, duos, and soli, enhanced by live music, expressed with the Italian subtlety France is crazy about.” And perhaps Sweden? Roy Andersson, after all, lives and works in Stockholm. Even more intriguing is the fact that he attributes his inspiration to a Peruvian poet, Nobel-laureate César Vallejo. So we have an Italian troupe performing at a French school in an American city a work based on a Swedish film inspired by a Peruvian poet. The whole event begs the question of universality and specificity in relation to concept, aesthetics, and appeal. Is there something global, after all, about our relation to space, movement, bodily gesture, and sound?

According to Tecnologia Filosofica, Canzoni del Secondo Piano is “a choreographic long take that portrays the invisible connections between souls in continual movement.” What an apt metaphor for the ways of the world in this 21st century! Add the analogy between cinema and dance theatre and we are hardly speaking metaphorically any more as far as Andersson’s work is concerned, especially this particular film with its meticulously timed and choreographed acting mounted upon finely crafted theatrical sets built and installed within Andersson’s own studio. Composed almost entirely of a series of extended takes shot by a stationary camera from a single position, Songs from the Second Floor requires the spectator to participate in much the same way as in viewing Canzoni del Secondo Piano upon the stage. Actions and gestures unfold before us within one frame but on multiple planes of the same perspective. As in everyday perception, our gazes shift as we choose the focus from among various contending points of interest. Then sound fluctuates from music to song to talk or any combination of these layers. Both the dance performance and the film make use of original music written specifically for the work and songs sung by the performers.

Tecnologia Filosofica

Tecnologia Filosofica, established by a group of independent artists living in Turin, Italy in 2000 (the same year that Andersson made Songs from the Second Floor), defines itself as:

A theatre community working in artistic research located at the boundary between theatre and dance, the dancers being interpreters but also authors of their work.

The company is horizontally built; there is no hierarchy, no permanent leader. The leadership can change from one project to another depending on individual involvement, in a permanent confrontation among the artists.

The concept/topic, which focuses on everyday life situations and social issues, emphasizes the asperities and contradictions of reality, always with an ironic point of view.

The company conceives of theatre as a total action, demonstrating a particular attitude toward the physical that questions the very meaning of “presence” within a space. Just as individual artists in the company might be on a collision course with each other at any moment in the creative process, the openness toward multiple points of view that characterizes Tecnologia Filosofica is also the basis of an international exchange of artists; the group often invites artists from abroad to present their work in Turin and share aesthetic practices in multidisciplinary residency projects. Funded by public cultural institutions in Italy since 2007, Tecnologia Filosofica also offers workshops abroad, such as the one on December 10, 2011 in Los Angeles, housed at the Instituto Italiano di Cultura, partnering sponsor for the December 9 performance, where participants experienced the physical, choreographic, and expressive patterns that inspired the choreography and composition of Canzoni del Secondo Piano.

Dance Theater

How can we not meet, no touching, so as not to imagine or feel what happens behind those doors ... and meanwhile, on the second floor, are playing the songs, words of love in the doubt of the evening, beating the time and the dance of human relationships.

Tanztheater becomes a space where we can meet each other.

Pina Bausch

When for the 1973/74 season, Pina Bausch was hired by Arno Wüstenhöfer to head the Wuppertal Ballet in Germany, she immediately renamed it “Tanztheater” after the term coined by Rudolf von Laban in the 1920s to signify freedom in the choice and means of expression for this performing art: dancers could also talk, sing, cry, and laugh upon the stage. Pina Bausch had learned from her mentor, Kurt Jooss in the modern dance movement, to balance the free spirit of dance innovators with the discipline of ballet, creative freedom with technical clarity of form. To these principles, Pina Bausch added an openness to other arts — music, opera, theatre, sculpture, painting, design, and photography.

Ankle-deep peat on the stage floor impeded the dancers footsteps and showed the tracks of their movement in Tanztheater’s 1975 Le Sacre du Printemps. A rainstorm glued costumes to skin as dancers crossed a river-like moat in the 2006 Vollmond. New concepts of staging permitted ways of exploring the body and its expressions through physical encounters with sets, properties, scenic elements. Dance theatre was developing in tandem with a particular type of filmmaking, one both lyrical and realistic at once. Just as Roy Anderson has enjoyed inspiration from painters and poets, dance theatre in the hands of Tecnologia Filosofica is now exploring inspiration from cinema. Likewise, just as Tanztheater Wuppertal affected both theatre and classical ballet as it influenced choreographers world-wide, Tecnologia Filosofica both draws from and extends itself to diverse cultural exchanges.

Francesca Cinalli, the choreographer of Canzoni del Secondo Piano and one of its five dancers, joined Tecnologia Filosofico in 1999 having trained in classical ballet at the Teatro Nuovo in Turino. She studied under the masters Robert Castle, Virgil Sieni and Giorgio Rossi, César Brie, and, significantly, Pavel Dudzinsky-Tanztheater Wuppertal (Pina Bausch). In 2006 she graduated from Gong Traditional Arts Institute of Genoa, Biennial School of Peoples and Cultures, having worked with mentors from Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

Songs from the Second Floor by Roy Andersson

Roy Andersson

My film is not surrealism or absurdism, as some people call it, but “trivialism” (though I touch on bigger, more philosophical issues at the same time). We all do up buttons, zip zippers, eat breakfast. Putting an emphasis on all this cuts people down to size, brings them more down to earth. We’re like the animals. Man is an animal.

Roy Andersson discussing Songs from the Second Floor

I work without a script and without a storyboard. I prefer to experiment like a painter, trying out the concept, the angle, the colors, the dialogues, the characters, the positions. That’s the advantage of a studio. And it’s not possible if you’re hindered by the pressure of the producers.

Roy Andersson to Nicolas Scmerkin for Repérages

Ironically, it is not the “animal” aspect of people (hatred, greed, brutality) that captivates Roy Andersson, but the humanistic side — responsibility, shame, bad conscience, regret. More than anything, his Songs from the Second Floor is a very moral work of art. Without subscribing to any organized religion, Andersson cites Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount as “an expression of absolute respect for the weak and vulnerable man who is threatened by forces that humiliate him and strangle his potential.” Andersson’s film itself is, in fact, just such an expression, drawn from an ensemble of actors (many enlisted from their normal jobs and professions in everyday life) who play their roles with unaffected authenticity as Andersson stages this thematic through-line.

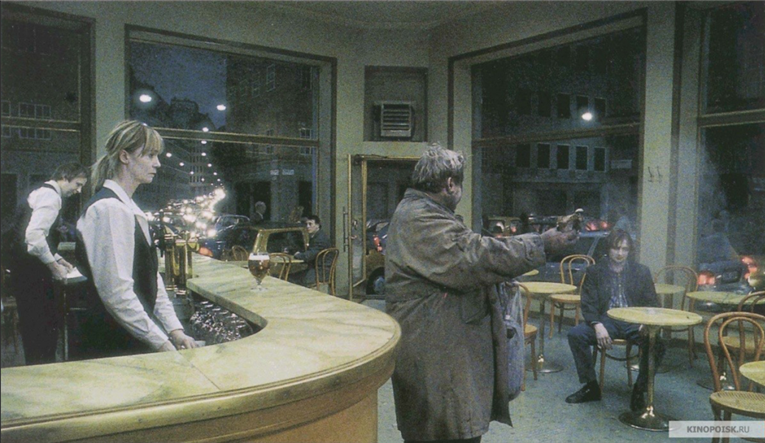

Songs from the Second Floor by Roy Andersson

Each scene was composed for its own discrete clarity and pared-down, exaggerated simplicity, shot from a wide-angle perspective for one uninterrupted single take, thereby heightening the tension within the frame. The sets were built in Andersson’s Studio 24 in Stockholm under his direction, where walls, furniture, vehicles, and props were all selected and arranged to create a proper balance of images according to the relative importance of each element. He then “choreographed” the actors within this composition, keeping in mind his commissioned original music (made via computer, orchestra, and choir) that would be simple, “naked,” and never technically overwrought, and that would work in counterpoint with the images.

Andersson’s film is indeed structured more like “songs” than a linear narrative — more like poetic vignettes that work together in an associative rather than a developmental way. Just as César Vallejo’s modernist poem, “Stumble Between Two Stars” provides an overarching leitmotif in the dialogue and thematically structures a series of five “Beloved be the one who sits” scenes (as the filmmaker refers to them), key visual motifs resonate from scene to scene: doors and windows of every size and shape but especially in repeated patterns graphically scaled within an immense frame; isolated chairs or benches in long and wide corridors or empty rooms and halls; a veneer of white make-up on the actors’ faces that reduces them to a standard look, a common stature; golf clubs turning up (mostly falling down or breaking) in bizarre settings; a man who must be hauled off, escorted out, by hospital orderlies every time he goes to visit his taciturn son in a mental ward and ends up raging in madness. In an apocalyptic film at the moment of the millenium, that man has burned down his own furniture show room to collect the insurance on his business as “things start to fall apart,” and an endless traffic jam signals a mass exodus, but nobody knows why. There are casualties, including that man’s silent son, who “wrote poetry ‘til he went nuts,” and a young girl, released from the same mental hospital only to be sacrificed to a higher force.

Canzoni del Secondo Piano

A door. It opens — in or out, and has windows, no less, through which we both see and imagine. Still it is an unspoken barrier, standing between us and life, each other, ourselves. Canzoni del Secondo Piano takes up the various dynamics and relationships played out daily in a surreal apartment house.

There are references in the performance that may never be attributed to Roy Andersson’s Songs from the Second Floor, much as they harmonize in tone with the life of a young couple in a working-class apartment on the outskirts of an urban center. In some vignettes (such as a celebration scene with party hats and poppers) the dance theatre draws from Andersson’s 2004 film, You, the Living, set almost entirely within such a housing complex, designed rather Tati-like to show multiple sectors of life simultaneously as layers of expressionistic acting, choreography with objects, and the music/sound/word score overlap.

It is the architectural portals that define the cityscape of Songs from the Second Floor that become the unifying image in Canzoni. Through the abstraction of windows (to the point of invisibility with the removal of “the fourth wall” as in epic theatre) we are all the more aware of the doors with windows we do see, the door being the elemental vehicle of the set — simple, clear, essential, and powerfully evocative of our endless transmigrations, our points of entry and departure, in daily life. The dancers climb it, ride it, unhinge it, carry it on their backs, transport it and transplant it. Only one other set property vies for centrality, and that is the chair.

Canzoni del Secondo Piano might look surreal in its mosaic-like, non-linear form and, on one occasion, even grotesque in a bizarre tangle of two bodies presumably striving for sexual contact, but for the most part it feels like ships in the night, a constant motoring without mooring of vulnerable souls in face of their own fragility. Like a choreographed sequence of paintings with idealized compositions, stripped bare of insignificant details all the while the minutiae of everyday life stand in for the deeper miseries of humankind, Canzoni locates itself in the banal, elemental strokes and gestures we make reluctantly, unwittingly, or passionately, even obsessively, to connect with each other. It treads lightly, but at moments, profoundly. A man might press the re-dial button on an old, desktop telephone twenty times in half a minute, or ring a doorbell incessantly with no answer, but he might also reach up to the heavens at dawn (or is it the encroaching dusk, the last salvation?).

The door, the window, and the chair make explicit reference to Andersson’s Songs from the Second Floor. Both in broad concept and in particularities of gesture, Tecnologia Filosofica interprets and re-casts the film’s physical phrasing upon the stage. The dance theatre is no more afraid of silence than the filmmaker, and the sound of a woman’s slap on a man’s face punctuates the silence here as it does in the film. Andersson shows us a big man from a very low angle literally “mopping the floor” with another grown man who won’t let go of his boss’s ankle as he begs not to be laid off from his job. The boss simply proceeds down the endless hallway dragging the man, stretched out on his stomach, until he can finally shake him off. In the dance performance, a door slam cues a male dancer to toss a female dancer across the floor; she lands on her belly. An occasional “freeze frame” of the action upon the stage, and dancers poised in the light of an on-stage projection, recall the cinematic source of the dance theatre’s movement and themes.

A particularly unique aspect of this production at the Théâtre Raymond Kabbaz was a lighting scheme that allowed a billowy curtain draped at the back of the stage to glow from pearl to platinum to peach as “sunlight” filled the air, drawing attention to a theatre ceiling of luminous blue sky and gray-white clouds. A male dancer climbed, reached, strived for that ascendancy while a female ran in circles, mostly falling down, as the sound of a jet taking off punctuated both the grasp and the failure of each.

A score that is performed live — played, sung, and spoken almost continuously by a leopard-coated chanteuse with two curlers in her hair strutting knee-high stiletto boots beneath a black mini-dress (Francesca Brizzolara) and a zebra-jacketed sound technician in black leather pants posing in pelvic tilt (Paolo de Santis) — riffs on familiar Italian songs and passages from renowned Italian musicians such as Mina, Giuni Russo, Modugno, and Ornella Vanoni, elaborating them in a new context with French text as well. Occasionally interacting as actors, the vocalist and musician face a video camera that at times projects them upon the back of the stage. Ranging from minimal instrumentals to soft techno-pop to French “boulevard” songs, Canzoni culminates with the surprise of a Mediterranean celebration as all five of the dancers finally “sit down” in chairs in a close circle facing each other, and clap their hands, laps and shoulders to mark time together in one common rhythm. The doors remain in an adjacent, tentative construction — touching, relying upon each other to “stand up,” but not adjoining. In an ending that cinematically quotes Songs from the Second Floor, the performance of Canzoni del Secondo Piano fades to black.

Canzoni del Secondo Piano by Tecnologia Filosofica

Choreography: Francesca Cinalli; Concept: Francesca Cinalli, Stefano Botti; Singer: Francesca Brizzolara; Music and Sound Stage: Paolo De Santis; Reworking of melodic and dramatic texts and songs: Francesca Brizzolara; Lights, Christian Perry; Video: Martin Cipriani; Designer: Alexander Baro; Stagecraft Consultant: Diana Lucio; Outdoor Look: Doriana Crema.

Dancers: Stefano Botti, Francesca Cinalli, Renato Cravero, Aldo Torta, Elena Valente.

Running time: 60 min.