12-1-12

If There Were No Music: “Four by Forman” Not to be Missed

By Diane Sippl

It was an opera, Smetana’s The Bartered Bride, and it was silent. The talkies had already been invented, but it so happened that the first movie I saw was a silent opera. It was as though I had offended my fairy godmother and she had decided that I’d get my first taste of art from an opera in which there was nothing to hear — just a lot of flamboyant gestures with no meaning.

Miloš Forman in “Miloš Forman, The Style and the Man” by Antonín J.Liehm

The closer you look, the more… you discover how things really are and, above all, you realize what language means — probably the most fundamental segment of culture that influences man.

Miloš Forman to Antonín J.Liehm, 1969, in Closely Watched Films

A film archive can be as valuable a reservoir of culture as a repertory theatre company: both, increasingly marginalized and eclipsed by the economies of advertising and the box office, can parade before us not only histories — of visual and performing arts and of nations, regimes, and their aesthetic movements — but also the raw material for theories, the originals that we now see as models for artistic expression. Lay actors playing themselves or improvising dialogue, 16mm location-shooting of everyday life, earnest performances turning into unconscious bathos, these were actually new in Prague in the early 1960s as deployed by the young Miloš Forman with a reinvigorated Czech irony.

The UCLA Film and Television Archive is presenting a particularly illuminating treat for film experts and novices alike in “Four by Forman,” a two-part retrospective of the auteur’s work in what was then Czechoslovakia, with Audition (1964) and Black Peter (1964) to be shown on December 1st and Loves of a Blonde (1965) and The Fireman’s Ball (1967) on December 15th. The prints, presented on loan from the National Film Archive in Prague as part of a nation-wide tour throughout the year, offer the rare chance to see the genesis of this important career, particularly in the first two works, hardly available for viewing elsewhere.

Miloš Forman is often called “the most important and influential director of the Czech New Wave of the 1960s.” If his first venture, Audition (1964), an assemblage of quasi-documentary footage, is commonly cited as the first instance of the “Czechoslovak Film Miracle,” then Black Peter (1964), his feature film debut that followed hot on the heels of Audition, allowed the nation’s cinema to burst into blossom as it never had before.

Superficially (dare I say?), both films are about youth — the escape from the obligations of encroaching adulthood and the rebellion against the “father,” the authority figure of the home, the workplace, or even the local amateur orchestra. Put another way, these two films are said to be clarion calls of the country’s social and cultural rejuvenation known as the “Prague Spring” when, between 1962 and 1968, the “thaw” of Stalinist control opened the floodgates of free expression.

As Miloš Forman celebrates his 80th birthday this year and the world looks back — past his subsequent Hollywood films that were so theatrical and conventionally lyrical (musicals such as Hair, period pieces such as Amadeus, literary adaptations such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) — his very early works of the 1960s appear utterly observational, factual, and objective in documenting the sights and sounds of a place in its time.

Yet if we look again, we can see that they had in store for us the deeper and more fundamental lyricism of Forman from the start. Revisiting his first films lets us discover this particular truth at the heart of his work, and not only that, but the key to the artistry that came to define an era.

The themes of Audition and Black Peter — the youthful rebellion against restraint, work, boredom, religion, conformity — were rebellious enough, but in conventional ways; what made Forman truly subversive was his style, a bold new film language that spoke for itself. In fact, the writer-director is said to have been against the regime of the time, but the “anti” label was pasted on him from outside, and it came long after he made both of these films.* Forman’s real “politics” lay in his cinematic sensibility, the paradoxical film language he developed quite organically. Via an inversion of the usual means of storytelling with its culmination of a linear narrative, by using a combination — or really a collision — of approaches that had traditionally been held as incompatible, Forman arrived at his means of expression for the screen; and ironically, it appears that he wasn’t so much against as with and of his time and place, in harmony with Czech culture, which gave his films their charm and appeal, their success.

Then the 16-millimeter Pentaflex movie camera came on the market. Heavy, awkward, noisy. But it had excellent lenses. Because… I didn’t know how to use a movie camera, I called Ivan Passer; he brought around Mirek Ondříček; and we went out together to shoot some film, just for fun — how people turn around and ogle the girls… and this was where it really all began.

Miloš Forman, in “Miloš Forman: The Style and the Man” by Antonín J.Liehm

Of all the films made by the world-renowned Miloš Forman, maybe it’s a little one, one of his first, that says it all. Shot as an addendum (it became 33 minutes long) to the 47-minute “Talent Competition” he had already shown to potential producers, “If There Were No Music” opens with the abrasive din of motorcycle engines revving up as James Dean look-alikes on the outskirts of Kolin suit up and head out in a race of the wheels, far from the Big Wheels of bureaucracy who have powered the communist machinery, but also far from the flying wands of the bandleaders who are drilling local musicians for the upcoming competition. The two segments of this diptych that came to be called Audition (a.k.a. Competition) are like matching bookends, each with its own cross-cutting and thematic juxtapositions that work more like crisscrossed exchanges of whimsy than parallel editing in a suspenseful story.

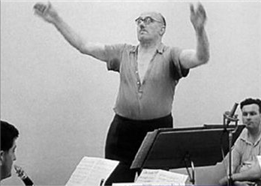

That uncorked amateur zeal is no wonder, coming from a maestro, sweaty undershirt stretched across his pot belly, who prods them along in their morning hangovers, “You are all soloists!” Sure enough, two are, at least as renegades — the one he “fires” because the youth prefers to go to the races, and the one he “hires” who left the competing band for the same reason. Both boys play it both ways, but the interesting question arises, which is the music? Is it the sagging chords of the middle-aged band members, chided by the platitudes of a pontificating maestro, or the sputtering roar of the teen bikers, in harmony with each other and their ritual?

“Music,” seemingly an abstraction belonging more properly to the experimentation with ideas taken up by Vera Chytilová, Jan Nĕmec, and Evald Schorm in the same era, was, in the hands of Forman, Passer, and Ondříček, an absolutely concrete metaphor — for language-in-the-making, with the rhythms and intonations of daily life arising from the poses, ruses, and antics of youths, the awkward insouciance, side glances and smooth moves of teens in their everyday maneuvers to situate themselves in their cohort via just the right expressions.

This metaphor extends aptly into the second half, “Talent Competition,” with a similar crisscrossing of vignettes showcasing everything that surrounds a singing performance at the popular Semafor (“Traffic Light”) Theatre in Prague in 1963 — coaching, make-up and costumes, auditions — but not the final result. In rehearsal a talented singer is badgered that her pitch is too low, though with her band she’s in her element singing the racy new “Locomotion” and captures the limelight. Yet in the audition proper, she tries three times to belt out her song, “Baby,” on cue with the pianist and finally withdraws in stage fright and silence. One of her competitors is so overly confident that she escapes work to try out and heaps her chords on the audience as if her future depended on it. And it does — she’s nowhere near “making music” and lands back with her boss after all. These intersections of conflicting articulations (and their lapses) are micro-performances peppering a generally observational cinema filmed mostly with a candid camera. And what that camera eye catches emerges metaphorically as the raw emotion of auditions not simply for the Semafor Theatre but for life, as the youths try out various styles of identity.

If in Audition Forman dappled documentary footage with fiction, then in Black Peter he presented fictional material as documentary. With non-professional actors, improvised dialogue, and considerable location shooting at real gatherings (even if they are spontaneously set up for the public in order to make the film), Forman follows sixteen-year-old Peter (Ladislav Yakim) through the non-events of his life. One of the biggest “dramas” is his misguided venture out of the supermarket where he is in training as a store detective and chases an innocent suspect through the streets. Spying is difficult for Peter to learn, much as it comes naturally when he ogles girls and especially when he fixes his gaze on a painting of a nude sent by higher-ups to decorate the store. He is particularly inept with Pavla, his crush, as he awkwardly shares with her this painting, a prop for flirtation, now folded up for transport after it fell from the wall and its glass shattered. Making “music” — making poetry, making love — seems to fall apart as well.

What works, despite Peter, is a wannabe friend’s invasion into his life, which begins with an entirely theatrical scene in which the lad teaches him how to properly say hello. “Ahoooj! Ahoooj! A-hoooj! the boy insists, while Peter does everything he can to shun him.** It’s music of another sort, Peter’s own “audition” — theatre meeting life, as Forman draws out the extraordinary in the ordinary, the normal obstinacy of youth expressing itself with pent-up vivacity, the insistence on language, the genuine, direct communication at eye level that Peter prefers to avoid. The collision course is set for the lyricism of language in-the-making, and it resounds in a compelling scene with Peter’s father and the same “friend” near the end of the film with satirical effect as Peter shuts down in silence, a statement in itself

Black Peter feels as though a roving camera on the streets of Kolin simply following the real routines of boys on and off their summer jobs in this provincial town. In fact the film was based on a novel by Jaroslav Papousek, Forman’s co-writer for his first three films. Forman memorized every word of the script they wrote in adapting the novel, and then he used these words to prompt the amateur actors in their situations as they often delivered their own dialogue, the details of the scene often yielding unintended irony. One actor, however, Vladimir Pucholt, who played Peter’s brick-laying tag-along, was then a fourth-year student at DAMU (Prague Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts). Recalled Forman,

I’d been waiting for a chance to work with Vladimir Pucholt. I’d found him when we were casting Grandpa Automobile. He was very young but had made an indelible impression during his audition and I never forgot him. He was just a little too old for the protagonist in Black Peter, so I cast him as the hero’s bricklayer buddy. I made three films with Pucholt, one of the most talented actors I have ever worked with.

Jan Vostrcil, who played Peter’s father, however, had no ambition of acting, “showing off”; Ivan Passer, Forman’s 1st A.D. and frequent co-writer, had discovered him accidentally as the bandleader in a rehearsal room and referred to him as “a volcano of humanity.” He had agreed to play himself in “If There Were No Music,” but Forman hooked him for Black Peter only by promising to add a brass band to the screenplay. Vostrcil would go on to “star” in The Fireman’s Ball. Věra Křesadlová was already a semi-professional singer and likewise bargained with Forman to get her entire trio and band to perform in “Talent Competition.” Furthermore, she went on to sing professionally in “real life” at the Semafor. Finally, she became Forman’s second wife.

An acute observation of the ironic details of mundane life; an intimate understanding of emotions, both projected and silenced; a keen sensitivity to the moment when solemnity melts into farce — these were the trademarks of the auteur that allowed him to lend his style, already cultivated early on in Prague, the Czech provinces, and Europe, to the largely theatrical films he would make in America.

Were those early days of filming comparable to the later years when Forman in the U.S. would create films that won him awards and fame?

This continuity between performance and life begins with Forman himself. Lacking filmmaking experience since he graduated from Prague Film Academy in Scriptwriting, he drew from his high school years as head of a theatre company staging classics of Czech satire and from his work with Alfréd Radok on The Magic Lantern, a mélange of film, slides, and theatre at the 1958 World EXPO in Brussels. For many months Forman drank in the world of showmanship and celebrity that was the real backstage life of his very realistic behind-the-scenes films about performers, known and unknown as such.

With his first three films, he worked relatively incognito: “no one knew anything about us, the films cost a few crowns to shoot, and nobody was all that impatient about them.” It changed with Fireman’s Ball, while he was still in Prague, and then forever when he left for Hollywood. He arrived with the murder of Martin Luther King, racial unrest, and student violence, which drove him to Paris just in time for the May ’68 student revolution. That chased him to Prague in the summer of the Soviet Invasion. By 1969 he surmised, “Take it from any side you want, reality is always so much more interesting than anything we can think up.”

So back to those streets and stadiums, amphitheaters and pubs, community centers and Saturday dances, riverbanks and skating rinks, rehearsal rooms and dressing rooms that he filmed in his early years as a quietly maturing cineaste: what vitality did he find in the lackadaisical youths who dodged rehearsals for recreation, and work for rehearsals, and any which way, were labeled lazy by their fathers? He told Antonín J. Liehm,

I know that, in my own life, a maximum of enthusiasm for work is born of endless days of boredom. The more you work, the further you get from that apparently lazy life you used to lead, a life that was immensely more productive than life among producers, scriptwriters, etc.

Forman, forever young, was forever seeking that language of youth, that “music” in the air, music-in-the-making.

* It wasn’t until 1973 that one of Forman’s films, The Fireman’s Ball, was entered onto a “banned forever” list by the Czech government.

** “Hallooooo!” According to the film’s lore, this scene helped coin a popular catchphrase in Czech that is still used today.

Audition (Competition, Konkurs)

Director: Miloš Forman; Producers: Rudolf Hajek, Miloš Bergl; Screenplay: Miloš Forman, Ivan Passer; Cinematographer: Miroslav Ondříček; Editor: Miroslav Hajek; Music: Jiří Šlitr, Jiří Suchý.

Cast: Jan Vostrcil, Frantisek Zeman, Vladimir Pucholt, Václav Blumental, Věra Křesadlová, Jiří Suchý, Jiří Šlitr, Markéta Krotká, Ladislav Jakim, Petra Brozka, Karla Marese, Frantiska Pokorneho.

B/W, 35mm (from 16mm for “Talent Competition,”) 79 min. In Czech with English subtitles.

Black Peter (Peter and Pavla)

Director: Miloš Forman; Producers: Jiří Šebor, Vladimir Bor; Screenplay: Jaroslav Papousek, Miloš Forman, from a novel by Jaroslav Papousek; Cinematographer: Jan Nemecek; Editor: Miroslav Hajek; Sound: Adolf Böhm; Music: Jiří Šlitr; Set Design: Karel Cerny; Costumes: Barbara Adolfova.

Cast: Ladislav Jakim, Pavla Martinkova, Jan Vostrcil, Vladimir Pucholt, Pavel Sedlacek, Zdenek Kulhanek, Frantisek Kosina, Josef Koza, Bozena Matuskova.

B/W, 35mm 85 min. In Czech with English subtitles.