12-5-09

A Lake at the AFI

FEST: Where

Downsizing Means Upscaling

It was cold enough to split stones. We noticed a foot-warmer, then an easel, then a man, swathed in three coats, his hands in gloves, his face half-frozen. It was M. Monet, studying a snow-effect.

The journalist who wrote this in 1868 was stunned by Claude Monet as an intrepid observer of nature who strived to place himself bodily in his subject, even if icicles grew on his beard or the high tide swept him off to sea. It’s the same artist who asked to be buried in a buoy.

All of this might seem like a strange way to open a discussion of a film made in 2008, albeit by a Frenchman devoted to portraying the winter surrounding a lake. In fact the look and feel of this film, including what we see happen on the screen and not just the enveloping atmosphere, bring a host of Russians to mind: the secret life of nature in all its tactile mystery that is Tarkovsky; the unquestioned, pre-conscious intimacy enacted with palpable sensuality that is Sokurov; the fluttering apprehension that is Dostoevsky; and each of these strokes producing its own glowing passion.

With the mere skeleton of a narrative

and sparse, cryptic dialogue that is also rough-hewn in its delivery, A Lake is even leaner in its character

exposition at the same time that it is profoundly archetypal. For a long time the slow, quivering descent

of a boundless tree to the ground and the aural-visual sensation that all

animal and plant life in the forest is preparing for it — a Kurosawan

myth-in-the-making as Dersu would take stock of it — is mostly what matters,

because it transfixes us, until, that is, we witness its human analog in a

scene that wrings from us unforgettable anxiety as the humble lumberjack Alexi,

our folk hero (Dmitry Kubasov), literally churns his way to the ground through

waist-deep snow, as if lathing his own grave by way of the convulsions of his

prone body in an epileptic fit.

Natalie Rehorova as Hege (The Daughter)

Philippe Grandrieux, writer-director-cinematographer of this spellbinding experience, quite tangibly places himself within his film, his camera drinking in a world he in turn molds from the sensations of light, mist and darkness and the ambient echoes or howls, gurgles or whispers. What realism there is in A Lake is not psychological but physical and metaphysical, not a charting and tracking of motivations, behaviors and relationships, but a mythical abstraction of them in the ur-form of a simple folk tale. The desires are primal, and they’re played out with the classical symmetry, scale, and proportion that lay the ground (and water) in a film such as Murnau’s Tabu.

The scope here, however, is both more sublime and more intimate, as if nature’s elements (mountains, snow, wind, trees) cast their own shadows that move these characters toward a shared interior fire. Their shelter is a hut in the woods with hardly a recognizable feature inside, but the trembling, subjective camera, collecting its focus, is empathetically magnetized to the eyes, lips, hair, and skin that compel these people to each other in mutual bonds of attraction and support. And in this parallel, primordial world with its own screen time and space — almost before individuals are given names and assigned demarcated roles — a stranger enters and shifts the harmonic balance by shoring up new gifts of trust and love. A blind mother, a tiny brother, and a returning father all emerge from the mist to share the logger’s loss of a sister, a first love, it seems, whose “voice is not the same any more,” he notes, as she ultimately bursts into song, piercing the soundscape of life as it was, and channeling her affection toward the lake she will cross with the love who will take her away.

A Lake is 87 minutes of sheer enigma as a film-going experience, and although Philippe Grandrieux was not able to attend the AFI FEST with his film, his lead actor, Dmitry Kubasov, spoke with programmer Robert Koehler and the audience following the screening and also with me two days later at the airport, both of us bound for Europe on the same plane.

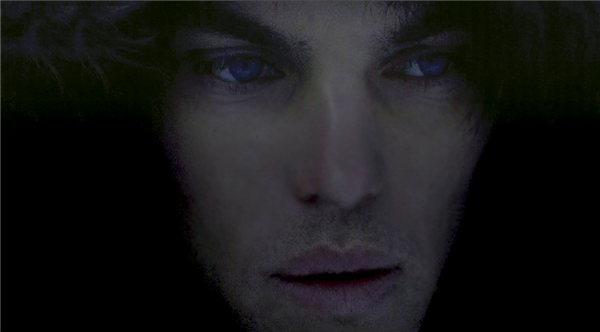

Dmitry Kubasov as Alexi (The Son)

"It seems that this director wasn’t looking for character acting. Were you surprised about the nature of the role you were asked to play?

Dmitry Kubasov I was surprised that a Russian actor was cast and that Phlippe was insisting that the actors not speak any French. I was also asking myself about the feeling behind the character. The answer was that he was supposed to be like a character out of Goya.

What did the director tell you about Alexi and how did he explain to you how to act the role?

DK He had actually written a script, but he wanted to keep an obscure ambience so that we would get intimate with the characters. There was one scene that gave him real trouble, and he was terrified. I was very cold. I left the scene and just cried, but then we were able to finish it. He was doing a good job, because the most important thing is to be genuine. Alexi’s relation to his sister was written in the script.

How did you know how to act in relation with nature?

DK We shot the film in Switzerland, and we spent 25 days in nature. We were trying to work fast, so we were shooting a lot every day and he was keeping the camerawork very simple, with few lights and little time for the lighting set-up.

Dmitry Kubasov as Alexi (The Son)

Did you research epilepsy, and if so, what did you learn and how did it prepare you for the role?

DK My cousin suffers from the disease, and I observed him in his village without telling him. I also did research on the Internet. Epilepsy always catches its victims by surprise, and their eyes always show their shock that an attack is happening.

Had you ever worked with Philippe Grandrieux before?

DK No, I hadn’t, but I had acted for other directors. I had lots of questions for Philippe, and I asked them all night ‘til he said, ‘Stop. Trust me, and play the part.’ All the scenes were 20-minute long takes. We went to the forest and started shooting. Due to his documentary background, I couldn’t tell if I was myself or Alexi. And when I went back to Moscow I couldn’t tell if I was Dmitry or Alexi.

Did it seem to matter as you were acting that Philippe Grandrieux was not only the director but also the cinematographer?

DK Philippe followed me intensely and went everywhere I went. He was always with me, behind me, next to me, and when the shoot was over, I saw him in the tree — a group of people were holding him. There was a very tender atmosphere through the whole film. It was very fragile and easy to break — a sacred feeling that needed trust. He used a handheld camera, so it was shaking. Philippe was reading Epstein and read about earthquakes and cameras shaking.

Is Philippe a fan of Russian directors? Why do you think he wanted a Russian actor?

DK Philippe loves Dostoevsky, and he was looking for the Russian soul of Dostoevsky, so casting required a lot of work for him. I’d never seen Philippe work before. Casting was held outside of Moscow, and Philippe sent me out to the forest to carry some wood. He seemed to be impressed that I began by taking off my watch. The next day I was told I got the part. Philippe was waiting for me while I finished shooting another film for two months. A Lake was supposed to take place in autumn, but by then it became winter. I graduated from college in Moscow and I'm a professional theatre actor. Now I’m studying to become a director of documentary films."

Alexei Solonchev as Jurgen (The Stranger)

Un lac (A Lake) may seem an obscure filmic experience for some, surely esoteric enough and, ironically, oblique for many viewers; others will find it penetrating to the bone. It is to the credit of AFI FEST Director of Programming Robert Koehler (new in the position this year) that such a film, at once poetically abstract and immediately sensuous, the result of experimentation in concept, form, and execution — indeed in the very definition, grasp and use of film as a medium — has made it to the screen at the heart of an industry town that flaunts its own age-old, self-proclaimed identity. To sit at Mann’s Theaters in the Hollywood and Highland shopping complex next to the king-of-kitsch Kodak Theater and behind its gauchely glorious predecessor, Sid Grauman’s Chinese (fronted by old footsteps in pavement just as new celebrities stroll the red carpet of this festival) is to wage a war of adjustment for taking in a film by Philippe Grandrieux, but it’s a war well worth fighting.

Outside of the “journey to the center of the earth” to park each day of the festival (though sooner or later, there is always a spot!), it’s difficult to find fault with other aspects of the event. Compared to some southern California film fests, where an out-of-towner (such as an L.A. resident) has to do handstands to score an advance single-ticket order at any price, this year’s AFI FEST broke all precedents and offered almost all tickets free with on-line or telephone reservations. Kudos to sponsor Audi for coughing up the budget for that and to the festival management, including Artistic Director Rose Kuo, for running with the ball.

If that meant cutting the number of films of the previous repertoire by a third and cutting the festival catalog to half the physical size, both the film program and its presentation in the catalog were better than ever this year. I was willing to sacrifice the fact that most films would be screened only once for the chance, finally, after all these years, to see a selection at all comparable to the international slate L.A.’s first cinema festival, FILMEX, offered over three decades ago. It seems to have taken all this time to “join the world” again, so to speak, in seeking out the best of critics as programmers (the way other festivals abroad do) and utilizing their knowledge and skills in moderating discussions with the filmmakers and writing the catalog. Robert Koehler’s vast exposure and experience serve him well, ranging as a critic from his (mandatedly) terse, lingo-laden, “industry”-tailored Variety reviews to his more loquacious and incisive Cinemascope discourses. He is free-thinking, astutely informed regarding world cinema, and highly articulate. The AFI FEST couldn’t ask for a better asset.

A Lake (Un lac)

Director: Philippe Grandrieux; Producer: Catherine Jacques; Screenplay: Philippe Grandrieux; Cinematography: Philippe Grandrieux; Sound: Guillaume Le Braz; Editing: Françoise Tourmen; Production Design: Olivier Raoux; Music: Liederkreis Op. 39 – Robert Schumann / “Mondnacht” (poem) by Joseph von Eichendorff, performed by Natalie Rehorova (voice) and Ferdinand Grandrieux (piano).

Cast: Dmitry Kubasov, Natalie Rehorova, Alexei Solonchev, Simona Hülsemann, Vitaly Kishchenko, Arthur Semay.

Color, 35mm, 87 minutes. In French with English subtitles.